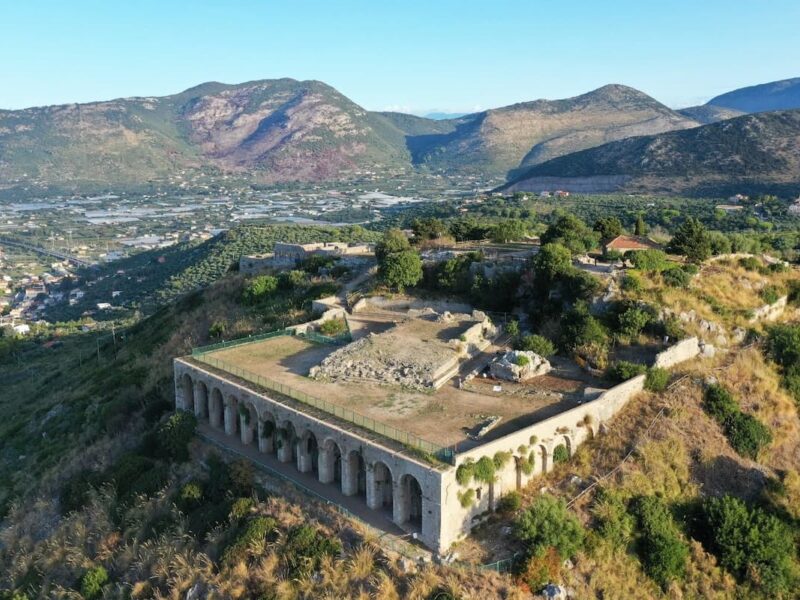

In County Meath, about 50 kilometers northwest of Dublin, lies the Hill of Tara. It is a modest elevation, only 155 meters high, but its location has influenced its role throughout Ireland’s history, making it a site of great significance both symbolically and strategically since prehistoric times.

The name “Tara” has ancient roots and is shrouded in myths and legends. Some suggest it comes from the ancient Irish “Teamhair” or “Temair”, meaning “elevated place”. Others believe it derives from the Celtic goddess of the earth and fertility, also named Tara.

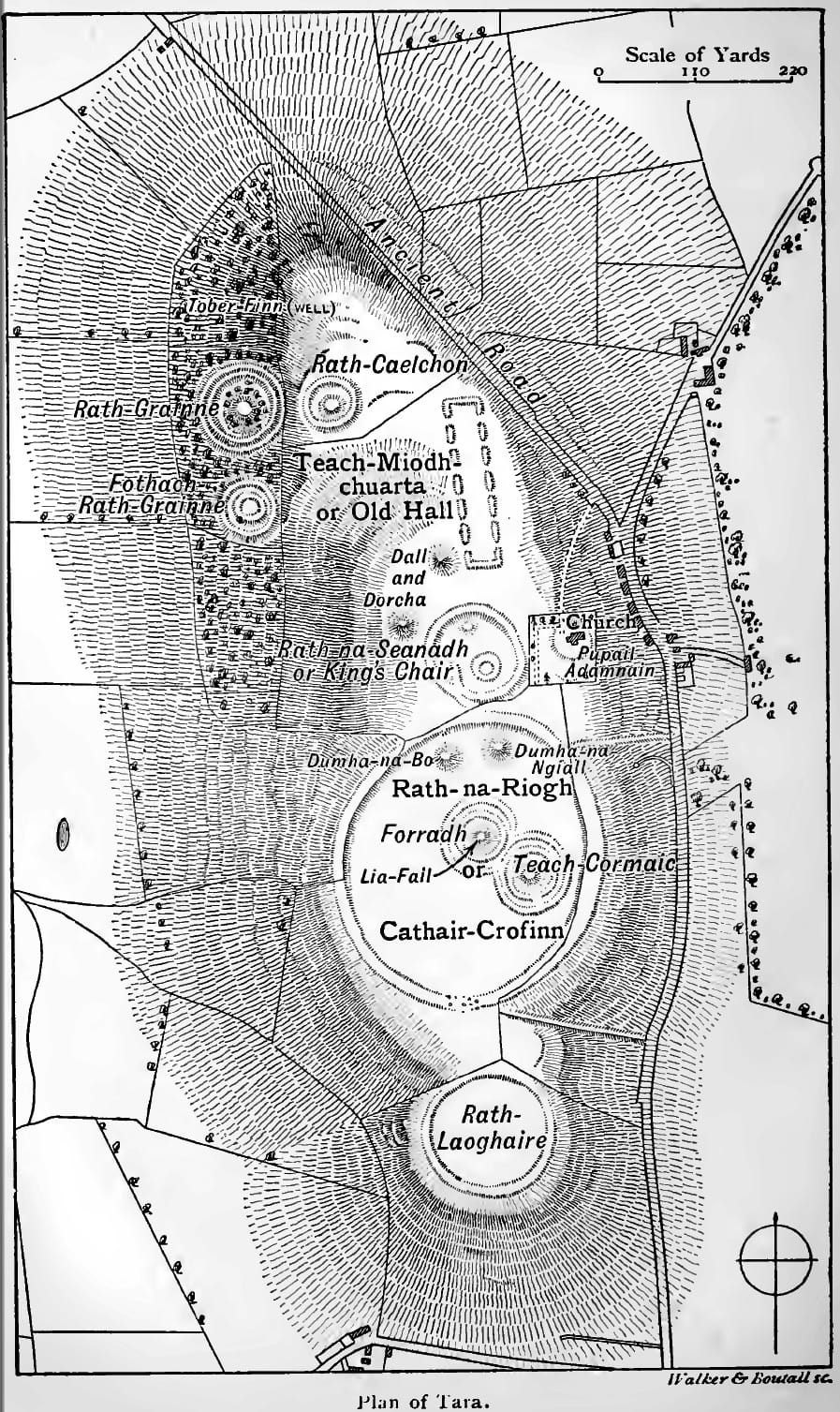

Regardless of the etymology and meaning of its name, Tara’s origins date back to the Neolithic period. Around 3200 B.C., the first of its preserved monuments was built, called Dumha na nGiall (Mound of the Hostages). It is a corridor tomb where hundreds of individuals were buried for over a century, reaching up to 300 during the Bronze Age, highlighting its sacred nature as a communal burial site.

The corridor entrance to the tomb has been confirmed to align with the sunrise on two occasions: early November during the Samhain festival, marking the beginning of winter, and early February during Imbolc, marking the start of spring.

Between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, a large double wooden circle, 250 meters in diameter, was constructed on the summit, surrounding the Mound of the Hostages. Around this circle, six smaller arched burial mounds were built. This wooden Woodhenge disappeared over time, leaving only the marks of the large posts on the ground.

During the Iron Age, large circular walled enclosures began to be built on the hill. The largest is called Ráth na Ríogh (Fortress of the Kings), with a circumference of one thousand meters, enclosing the Mound of the Hostages.

Inside the Fortress of the Kings are two oval-shaped structures, called Teach Chormaic (House of Cormac) and Forradh (Royal Seat). The latter houses the famous Lia Fáil (Stone of Destiny), on which, according to tradition, the High Kings of Ireland were crowned from the first, Brian Boru in 1001, to Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair, who died in 1198 and was the last. It was said that the stone had been brought to Ireland by the mythical Tuatha Dé Danann and would cry out when a legitimate king placed his foot upon it.

In another circular enclosure, called Rath na Seanadh (Ring of the Synods), which once also contained a wooden structure, Roman remains dating from the island’s occupation between the 1st and 4th centuries A.D. were found.

Other walled enclosures include Rath Laoghaire (Fort of Laoghaire), located on the southern edge of the hill, where legend has it that the king of the same name is buried upright. And Claonfhearta (Sloping Trenches), to the northwest, containing several burial mounds.

At the northernmost point is Teach Miodhchuarta (Banquet Hall), a rectangular structure that was probably a monumental avenue leading to the summit of the hill. It is one of the last structures built.

Abundant archaeological evidence demonstrates that Tara was the most important political and religious center in ancient Ireland. But it is not just a collection of monuments from ancient times; it is a symbol of Irish identity, and as such, over the centuries, it has been the setting for crucial events that have shaped the fate of the island.

From the Bronze Age to the arrival of the Normans, Tara has been a focal point for royalty and consequential decision-making.

Medieval Irish literature presents Tara as the setting for much of Celtic heroic epic, where mythical ancestors dwelled, and ceremonies and festivals such as Samhain took place every November 1st, marking the onset of winter. Additionally, according to tradition, Tara is the convergence point of five ancient roads or causeways, connecting it to all regions of Ireland.

In the 12th century, Tara experienced a decline in its political significance with the Norman influence expanding in Ireland. Although the Hill of Tara continued to be a site of historical interest, its central role in Irish politics diminished.

This exceptional site, with its unique blend of mysticism and reality, traditions and legends, continues to harbor mysteries. Currently, up to 20 structures or monuments are visible, but beneath the surface, through geophysical studies and aerial photography, at least another 60 have been detected, waiting to reveal their stories.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on November 23, 2023. Puedes leer la versión en español en La Colina de Tara, el lugar más sagrado de Irlanda, está llena de monumentos prehistóricos, romanos y medievales

Sources

Woodhenge Tara (Knowth.com) | Petrie, G. (1839). On the History and Antiquities of Tara Hill. The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, 18, 25–232. jstor.org/stable/30078991 | Hill of Tara (Heritage Ireland OPW) | Wikipedia

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.