Every September 12th, the Indian armed forces celebrate a festival called Regimental Battle Honours Day. The regiment referred to in the name is the Sikh regiment, the protagonist of a heroic episode in 1897 during the Second Anglo-Afghan War. During that time, 21 men from a small detachment defended their position against thousands of enemies, losing their lives but entering into glory. This heroic action, studied in schools in Punjab and also commemorated by the British Army, is known as the Battle of Saragarhi.

The British Empire had invaded Afghanistan in 1878 for the second time, as it had done before in 1839 to secure control of a territory coveted by the Russians. This territory was the first step for the Russians to have a seaport in the region, with the next being the northwest of India (what is now Pakistan). This large-scale chess game was known as the Great Game, and in its first phase, the British East India Company played a significant role. However, after suffering a defeat and extermination during their retreat from Kabul, London decided to abandon the country.

In 1855, a peace agreement was signed with Emir Dost Mohammed Khan. Still, in the last quarter of the century, following the Congress of Berlin, the Great Game intensified for control of Central Asia. Sher Ali Khan, Dost’s son who succeeded him, found himself pressured by both sides. Despite his refusal to be received, the Russians imposed a diplomatic delegation seeking to influence Afghan politics. When the British tried to do the same, they were prevented, leading to a casus belli. The British succeeded on the battlefield this time, and two years later, through the Gandamak Treaty, they turned Afghanistan into a protectorate, imposed a favorable emir, and withdrew their troops.

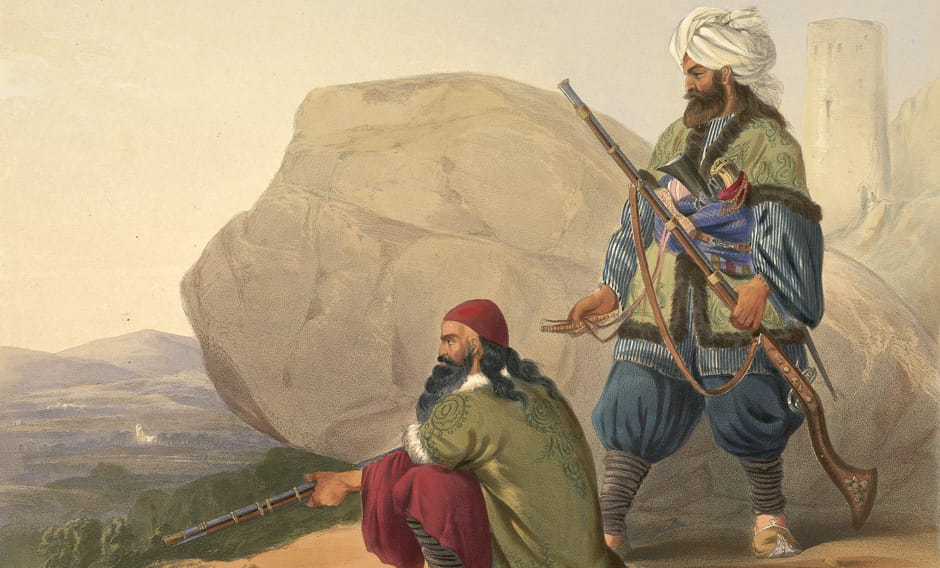

However, some border regions were detached and annexed to British India. One of these regions was Tirah in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, strategically valuable because it housed the Khyber Pass. This mountain pass connected the Peshawar Valley to Indian territory through the Spin Ghar mountains, serving as the route for the army to move between countries. The original inhabitants, the Tirahi, had been expelled in the 17th century by the Pashtuns, three tribes of which would lead an uprising in 1897: the Afridis, Orakzais, and Chamkanis.

All three were up in arms despite the fact that, according to custom, they were subsidized by the Raj (British government in India) to keep them quiet; moreover, the guarding of the Khyber Pass had been left in the hands of a regiment composed exclusively of Afridis, from whom no one expected disloyalty after sixteen years of service. However, it was a tense peace with occasional attacks and it was enough that some news spread to inflame tempers. On the one hand, the Turkish victory over the Greeks; on the other, the publication by the emir of a religious work of a markedly anti-Christian nature brought several chiefs together under a charismatic leader; in the background, discontent over a punitive campaign carried out three years earlier against another Pashtun tribe, the Waziris, who had refused to accept the Durand Line (a new frontier) because it brought them within the British sphere of influence.

Under a charismatic leader, and with underlying discontent over a punitive campaign against the Waziris three years earlier, the Afridis seized control of the Khyber posts, and the Orakzais did the same in the Samana Range, an area with another crucial pass, the Chagru Kotal, essential for accessing the city of Peshawar. Dargai, a key stronghold dominating the path, became the focal point of the conflict. Eleven forts, including Fort Lockhart and Fort Gulistan, were built on its ridges between 1834 and 1837 by Ranjit Singh, the head of the Sikh Empire. Around 5,000 Afghan warriors, led by Gul Basdah, gathered there, with the total number reaching 10,000 or 20,000. The British hastily organized their troops to face the Mohmands, another Pashtun tribe northwest of Peshawar.

In June, the Mohmands took up arms, followed by the usually peaceful Swatis in July and the Afridis in August, capturing all the Khyber forts. Sir Bindon Blood was tasked with quelling the first uprising, which he successfully accomplished on October 5th, despite having a small force called the Malakand Field Force, consisting of 1,200 men, including Second Lieutenant Winston Churchill. Churchill, who was serving as a war correspondent, later recounted the events in his book “The Story of the Malakand Field Force. An Episode of Frontier War“.

Meanwhile, not far from there, in the Samana Range, the mentioned episode unfolded. For the 1894 campaign against the Waziris, the 36th Infantry Regiment was created, exclusively composed of Sikh soldiers from the Jat sub-group. Sikhs had joined the ranks of the British East India Company after the Anglo-Sikh War of 1846. In August 1897, under Lieutenant Colonel John Haughton’s command, five companies of that regiment were sent to positions in Samana, Kurag, Sangar, Sahtop Dhar, and Saragarhi.

Saragarhi had a unique mission: it was built on a prominent rocky crest to communicate via heliograph with Fort Lockhart and Fort Gulistan, which were separated by only a few kilometers but not visible due to the rugged terrain. Saragarhi was modest, consisting of only a handful of small houses, a signal tower, and a perimeter wall, making it unsuitable for a large garrison. It was assigned to 21 Sikh sepoys, led by Havildar (Sergeant) Ishar Singh, who were returning to Fort Lockhart after being sent to Fort Gulistan as reinforcements to repel Afridi attacks between September 3rd and 9th.

Around 9:00 on September 12th, they were surrounded by thousands of Afghans launching an attack. The defenders requested help from Fort Lockhart via heliograph, but Lieutenant Colonel Haughton replied that he couldn’t send assistance. With no other option, they had to resist or die, as they rejected surrender offers. The Sikhs managed to repel two assault attempts by firing in sections, holding on for three hours. Then, the clever enemy set the surrounding vegetation on fire to conceal their movements and approach with fewer casualties. The sepoys, whose numbers had been halved, took cover behind the walls.

It was around 14:00, and ammunition was running low, with an attempt to bring more from Fort Lockhart failing. Ishar Singh, unable to stand, ordered to place him on the front line with the bayonet fixed to his rifle, as there were not enough men to defend all points of the perimeter. As a group of Afghans concentrated at the gates, another breached the wall like a wave. It was the most desperate moment, with a frantic and fierce hand-to-hand fight inside the compound, leaving four sepoys fighting back to back. In the end, reality prevailed, and the Sikhs were massacred by the overwhelming human tide.

Gurmukh Singh, the heliograph operator, was the last to fall. After sending a final message to the fort explaining what was happening, he took up his rifle to defend the signal tower where he sought refuge. According to legend, he took down about twenty adversaries and forced them to set fire to the building to eliminate him. The legend is embellished with a phrase attributed to heroes before losing their lives: “Bole so Nihal! Sat Sri Akaal!” It was the traditional Sikh greeting, also used at the end of religious celebrations and as a war cry. One would shout the first phrase, and others would respond with the second. It’s challenging to translate, but it roughly means “He who speaks shall be blessed. The glorious Truth is eternal”.

Similar to the Battle of Thermopylae, the sacrifice of those 21 men allowed reinforcements with artillery to reach Fort Gulistan on the night of September 13th. This not only enabled the defenders to hold it but also to recapture Saragarhi the next day after intense bombardment from the ridge. The scene was devastating because the 21 sepoys had died, but alongside their bodies lay around 600 Pashtuns (not counting numerous wounded crawling), most killed by cannon fire and about 180 by the Sikhs.

Meanwhile, the Punjab Army Corps, led by Sir William Lockhart, advanced rapidly: 34,882 troops, including the 2nd Gurkhas and the Gordon Highlanders (where piper George Findlater became famous for playing to encourage his comrades even after being wounded, earning the Victoria Cross). They swept the Afghans out of Dargai on October 20th, proceeding with what is known as the Tirah Campaign. It concluded in December with just over 500 of their own casualties, and in April 1898, following negotiations with the Pashtuns, the expeditionary force was disbanded.

All those who fell in Saragarhi were from the Majha region in Punjab and were posthumously awarded the Indian Order of Merit, the most prestigious medal for a sepoy at that time, equivalent to the Victoria Cross for the British. Their feat was immortalized in the Khalsa Bahadur, an epic poem by writer Chuhar Singh published in 1915, serving as the Sikh version of Tennyson’s unforgettable verses on the Charge of the Light Brigade. Those verses seem fitting to conclude this account:

Was there a man dismay’d? / Not tho’ the soldier knew / Some one had blunder’d: / Theirs not to make reply, / Theirs not to reason why, / Theirs but to do and die (…) / When can their glory fade?

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on July 30, 2019. Puedes leer la versión en español en Saragarhi, la batalla en la que 21 sijs se enfrentaron a miles de afganos

Sources

Dhruv C. Katoch, The Battle of Saragahi | Kiran Nirvan, 21 Kesaris. The Untold Story of the Battle of Saragarhi | Vidya Prakash Tyagi, Martial races of undivided India | Coronel Kanwaljit Singh y Mayor H S Ahluwalia, Saragarhi Battalion. Ashes to glory | Robert Johnson, The 1897 revolt and Tirah Valley operations from the pashtun perspective | Wikipedia

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.