There are historical figures who have gone down in history more for some inconsequential anecdote than for the significance they had in the context in which they lived. This is what happened with a priest who lived between the 15th and 16th centuries, was the master of ceremonies for Pope Leo X, organized three conclaves for the election of several popes, and left testimony of historical episodes of his time that he witnessed or knew closely, as interesting as the Sack of Rome or Henry VIII’s request for divorce. His name was Biagio da Cesena, and today he is better known for his insistence on erasing the nudity that Michelangelo painted in the Sistine Chapel.

Originally called the Cappella Magna because it was the largest chapel in the Apostolic Palace of the Vatican, the official residence of the Pope, the Sistine Chapel owes its name to Sixtus IV, who ordered its construction between 1475 and 1481 on top of a previous medieval one. It is the place where cardinals still gather in conclave when a new pope needs to be elected, although it is generally used as a museum and is often crowded with tourists who come to admire its pictorial decoration. This artwork is the work of various important artists, such as Pietro Perugino, Piermatteo d’Amelia, Sandro Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, Pinturicchio, Cosimo Rosselli, Bartolomeo della Gatta, and Luca Signorelli, among others.

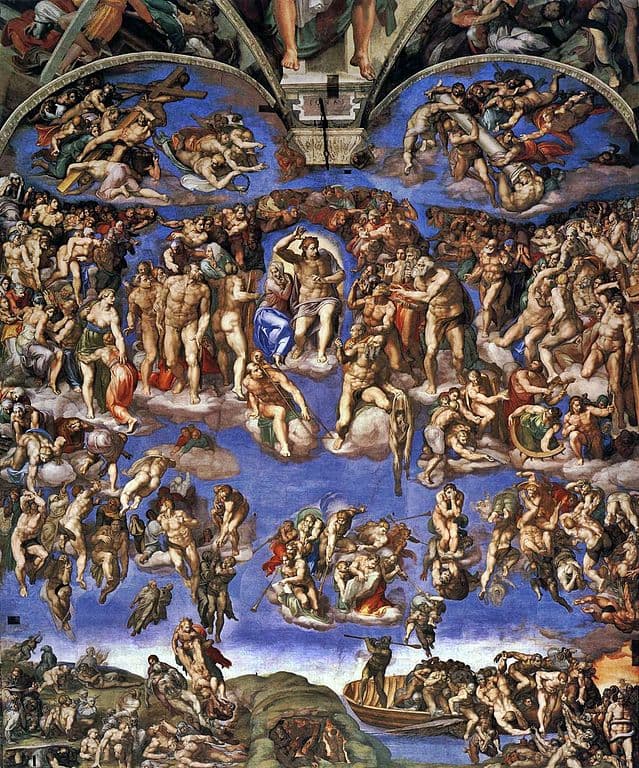

However, the most spectacular part belongs to Michelangelo, who was commissioned by Pope Julius II to redo the painting of the ceiling, as the one by d’Amelia was irreparably damaged by cracks. The work took him four years and was completed in 1512, but in 1536 Pope Clement VII summoned him again to return from his native Florence, where he had gone back, and to paint the altar wall. The artist placed there his famous fresco of the Last Judgment, which he completed in 1541. Although it is now considered a masterpiece, during its creation, there were heated debates about the morality of depicting so much nudity in a sacred space where the representative of God on Earth was also elected.

One of those who expressed disapproval was Cardinal Gian Pietro Carafa. A member of a distinguished Neapolitan family, he had held the position of apostolic protonotary while studying the classics, which, they say, he memorized. Aside from serving as papal master of ceremonies, he held various positions, traveling to Henry VIII’s England as legatus a latere (pontifical legate) and to the Spain of Charles I as apostolic nuncio. He also founded the Order of Regular Clerics and worked on drafting the condemnation of Luther, publishing a 1520 treatise on the matter titled De Justificatione.

He served under five popes: Leo X, Adrian VI, Clement VII, Paul III—who made him a cardinal, prefect of the Holy Office, and Archbishop of Naples—and Julius III, whose death was followed by Marcello II. The latter did not have time to serve because he died twenty-one days later, in 1555, prompting the need for another conclave; the chosen one was Carafa, who took the name of Paul IV. His eighty years of age did not prevent him from exercising an energetic mandate: following the impulse of the Council of Trent, convened by Clement, he empowered the Inquisition to fight heresies—particularly Protestantism—established literary censorship (he promoted what would later become the first Index of Forbidden Books), and expressed open hostility toward the Spanish for their power in Italy.

Paul IV alternated nepotism with the imposition of strict moralism which, as mentioned earlier, had led him to clash with Michelangelo when he was still a cardinal, spurred on by critics who organized a harsh campaign against the Sistine Chapel frescoes, considering them obscene and inappropriate because the figures displayed their genitals. If Michelangelo’s depiction of Adam on the ceiling reaching out to God was bad, the new sacred images were worse, especially the completely naked Christ in Majesty (not to mention without a beard and with an unusual angry expression).

Michelangelo was also accused of doctrinal errors, putting him on the brink of heresy and therefore being prosecuted by the Holy Office. This didn’t happen because aesthetic disqualification prevailed. The grammarian Ludovico Dolce opined that the Florentine’s paintings lacked “a certain tempered measure and certain suitability” compared to Raphael’s, and some even said that “if you’ve seen one Michelangelo figure, you’ve seen them all”. Both religious and secular critics weighed in: the poet Pietro Aretino (who suggested “making a bonfire with the work”), Archbishop Ambrogio Catarino, the priest and writer Giovanni Andrea Gilio, and Monsignor Sernini (who was also the ambassador of Mantua). But the most persistent and insistent was the aforementioned master of ceremonies, Biagio da Cesena.

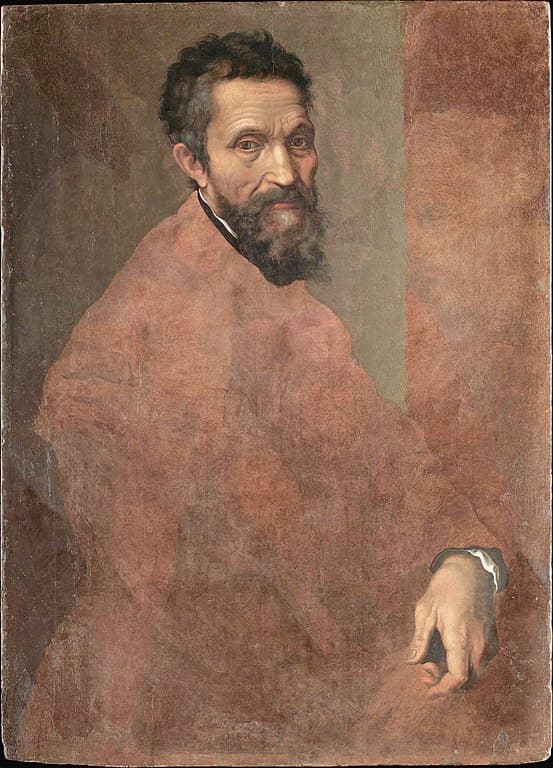

Biagio da Cesena, born in the Adriatic town of the same name in 1463, came from the noble Guelph family, the Martinelli. A graduate in utroque iure (a double degree in civil and canon law, typically Catholic), he worked as a lawyer or perhaps a notary in Rome from a young age, which helped him stand out and catch the attention of the papal master of ceremonies, Paride Grassi, who in 1518 recommended him as his colleague (it was a tri-head position) with the approval of Cardinals Bernardo Dovizi (who, known as Bibbiena, was a playwright aligned with the Medici) and Andrea della Valle (personal physician to Alexander VI). Biagio da Cesena, who would eventually become prefect of the ceremonials, had to organize three conclaves: those of 1522, 1523, and 1534, in which Popes Adrian VI, Clement VII, and Paul III were respectively elected.

And indeed, the Magister Caerimoniarum Apostolicarum (now Master of Pontifical Liturgical Celebrations), who held his position for five years—renewable—had the task of assisting the Pope and the cardinals in ceremonies, consistories (meetings of the College of Cardinals), the taking possession of titular churches, and liturgical acts in general. He was the one responsible for exclaiming “Extra omnes!” (“Everyone out!”), the phrase used to clear the Sistine Chapel when the conclave to elect a Pope begins, leaving only the cardinal electors inside.

Moreover, starting especially in the 15th century, masters of ceremonies would often write a kind of journal detailing the course of their activities, which have become true chronicles of the era. In that vein, Biagio da Cesena left detailed descriptions of various events that closely affected him, such as the Sack of Rome (the assault on the Eternal City by imperial troops, from which he had to take refuge in castel Sant’Angelo), the stormy diplomatic negotiations between Charles V and Francis I (who were clashing for control of Italy, among other things), and the thorny issue of the annulment of the marriage between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, which led to the Anglican Reformation.

Returning to Michelangelo’s frescoes, they were already far advanced when murmurs began to arise, crystallizing historically in what became known as the campagna delle foglie di fico (”fig leaf campaign”), as critics called for covering the nudity of the figures in the traditional manner. Giorgio Vasari, the famous architect and painter, considered one of the first art historians, published a work in 1550 titled Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori (“The Lives of the Most Excellent Italian Painters, Sculptors, and Architects”) in which he recounts how this controversy erupted:

Messer [Monsignor] Biagio da Cesena, master of ceremonies and a scrupulous man, who was in the chapel with the Pope, when asked what he thought, said that it was very inappropriate to have made so many naked people in such an honorable place, who so indecently displayed their shame, and that such work belonged in public baths and taverns, not in the chapel of a Pope.

Michelangelo, known for his difficult character, was not someone likely to take such criticism lightly. He had already had disputes with Julius III over the delay in completing the vault’s paintings, but not over the nudity in the Last Judgment, as that pope was tolerant in that regard (in fact, he was accused of being “pueribus amoribus implicitus”, that is, entangled in amorous affairs with his young nephew Innocenzo). So, the pontiff ignored the recommendation made by some to destroy the painting. But now, the artist truly felt his pride wounded by what he saw as a foolish and uncultured critique, and he decided to settle the score in a clever and subtle yet lasting way. Vasari explains:

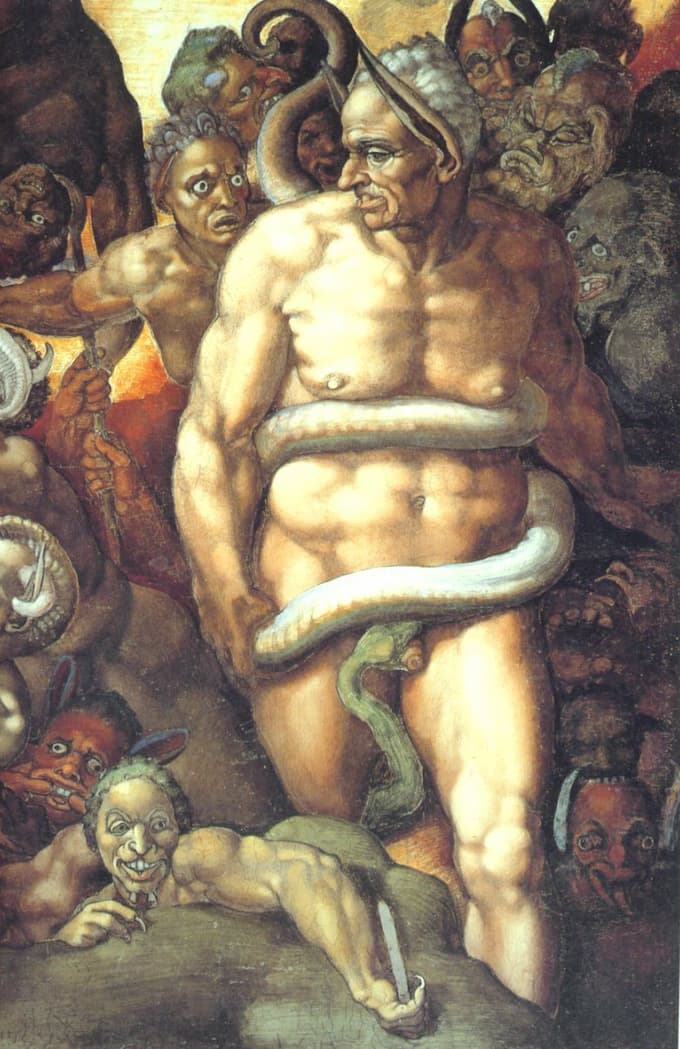

Angered by this, Michelangelo, wanting revenge, soon after [Biagio di Cesena] left, painted him from life, without changing him in any way, in Hell, in the figure of Minos, with a large snake coiled around his legs amid a mountain of demons.

Indeed, on the bottom right of the wall, dedicated to the damned souls, he painted the famous King Minos as the judge of the underworld, depicted with donkey ears, symbolizing supreme stupidity, and with a naked body, his genitals being bitten by a snake coiled around his legs, which was actually his own tail. To top it off, Michelangelo gave the monarch the face of the lustful cardinal, who, obviously, was not amused and went to complain to the Pope, requesting that Michelangelo be ordered to erase the personal affront. A double insult, since when Mass was celebrated in the chapel, it was inevitable that everyone would see him in Hell, in such a humiliating condition.

However, Paul III rejected the request, displaying—he, at least—a good sense of humor. Vasari doesn’t record the Pope’s response, but the humanist Ludovico Domenichi does: “My dear son, if the painter had put you in purgatory, I could get you out, for my power extends there; but you are in Hell, and I cannot”. Thus, Michelangelo scored his first victory. But the war would continue, and in the next battle, he would not emerge so unscathed, for the times were changing, and since 1549, Pope Pius IV, an old friend of Carafa, was giving new impetus to the Council of Trent. And in January 1564, when the artist was focused on completing the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica, the Council ordered the private parts of the figures in the Last Judgment to be covered.

The artist chosen for this task was Daniele da Volterra, a prestigious Tuscan painter considered one of the best representatives of Renaissance Mannerism, and the author of a highly esteemed painting in his time, The Descent from the Cross, located in the church of the Trinità dei Monti. Ironically, he completed it based on sketches by Michelangelo, for whom he served as a secretary. Michelangelo was very upset because, at the time, it was an irreversible action, as his fresco would be covered by oil paint. However, his anger did not last long because he died the following month.

Volterra could not avoid going down in history with the nickname Il Braghettone (“The Breeches Painter”), despite the fact that he tried to be as respectful as possible and alter the master’s work as little as possible, choosing to cover the figures with small flowing drapes rather than clothing them. The only exception was the pair of Saint Blaise and Saint Catherine of Alexandria, which was especially scandalous because they appeared in a posture too similar to one of sexual intercourse. Volterra covered them and changed the direction of their gazes to make the scene less explicit. However, he died in 1566 without completing the task.

Consequently, two other artists were appointed to replace him: Girolamo da Fano and Domenico Carnevali, considered lesser in comparison. They did finish the assignment, but the moralizing legacy left by Trent, embodied in the Counter-Reformation, insisted on the idea of erasing or covering Michelangelo’s paintings, which were also considered ugly because the women were too muscular (something due to the fact that the Florentine artist found the male body more beautiful). El Greco himself, for example, offered to make the changes, although he was not heeded. And while that obsession did not completely disappear (as late as the 18th century, the painter Stefano Pozzi covered the wall with varnish), by the end of the first quarter of the 19th century, art finally prevailed.

Moreover, starting in 1980, the paintings in the Sistine Chapel underwent a cleaning operation to restore their original colors, and in 1994, they were reopened to the public, fully restored. Among the considerations was the removal of the censoring additions, but in the end, the choice was made to leave Volterra’s, da Fano’s, and Carnevali’s additions as a testimony to the Counter-Reformation, while removing the later ones. The times had changed, and no less than Pope John Paul II described the frescoes of the Last Judgment as “the sanctuary of the theology of the human body”.

These are words that Biagio da Cesena, without a doubt, would have found hard to comprehend. He didn’t even live to see Volterra’s patches. He died in late 1544 after rejecting the bishoprics of Bertinoro and Forlimpopoli, offered by Paul III, as he didn’t feel strong enough. He is buried in the Roman basilica of Saints Celso and Giuliano, near the bridge of Sant’Angelo.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on October 10, 2024: Biagio da Cesena, el cardenal al que Miguel Ángel caricaturizó en la Capilla Sixtina por criticar los desnudos de sus pinturas

SOURCES

Giorgio Vasari, Vidas de los más excelentes pintores, escultores y arquitectos

Lodovico Domenichi, Historia di detti et fatti notabili di diversi Principi & huommi privati moderni

Massimo Ceresa, Biagio Martinelli

Wikipedia, Biagio da Cesena

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.