In an era long before any concept of dignified treatment for defeated enemies, during a time when losing on the battlefield often opened the door to the most bloodthirsty barbarities, in the Middle Ages, there was an event that even exceeded the norm and echoed throughout history as a chilling reminder of that brutal reality of war. The protagonist was Byzantine Emperor Basil II, who earned the rather unattractive nickname Boulgaroktonos (Bulgar-Slayer), after ordering the blinding of the thousands of Bulgarian captives he took at the Battle of Kleidion.

In the early 11th century, the Byzantine Empire was exerting pressure toward the west and north, specifically over Bulgaria, the same way it was being pressured from the other side by an expanding Fatimid Caliphate. This was not a new situation; its origins could be traced back four centuries, when Asparukh, a khan of the Dulo clan from the Ukrainian plains, took advantage of Constantinople being tied up—besieged by troops from the Umayyad Caliphate of Baghdad—to lead his people across the Danube and settle them in a region called Ongala, which roughly corresponded to southern Bessarabia.

Those proto-Bulgarian invaders numbered close to a million, too many to expel effectively. So Emperor Constantine IV, once freed from the Muslim siege, allowed them to stay on the condition that they concentrated in a fortified and monitored settlement. However, Constantine fell ill and had to return to the capital, which demoralized the soldiers tasked with watching over the Bulgarians. Asparukh, noticing this weakening, took advantage and defeated the Byzantines in 680, continuing his advance into Byzantine Thrace.

The emperor chose to reach an agreement, accepting their presence and hiring that army to fight against the Muslims. This is considered the birth of the First Bulgarian Empire. Of course, relations between the two sides were doomed to deteriorate, and the inevitable clashes led to war several times, turning them into rivals. Bulgaria expanded, reaching Transylvania in the north and the Greek peninsula in the south, seriously threatening the Byzantine Empire during the reign of Tsar Simeon I. However, in 968, things changed: Prince Sviatoslav I of Kievan Rus, who had launched an aggressive military expansion campaign by conquering Khazaria, turned his sights westward and, answering a proposal from Emperor Nicephorus II, began a campaign against the Bulgarians.

Sviatoslav’s troops, consisting of six thousand Pecheneg mercenaries (also called Patzinaks, a semi-nomadic people from the Central Asian steppes), defeated Bulgarian Tsar Boris II at the Battle of Silistra, taking the northern part of the country. Then, cleverly manipulated by the Byzantines—true masters of intrigue—they turned against Kiev, forcing the prince to return and lift the siege on the city. Thus, Nicephorus II emerged as the great beneficiary, as he kept what had been taken from Bulgaria and even captured Boris II in 971. Sviatoslav did not give up and, after reorganizing, returned to the offensive, taking Thrace, but the conflict dragged on. Nicephorus was succeeded by John I Tzimiskes, who eventually defeated the Kievan prince, forcing him to withdraw permanently (incidentally, Sviatoslav was later assassinated by a Pecheneg khan paid by the emperor).

Boris II was forced to renounce the Bulgarian throne, and the eastern half of his country fell under Byzantine control, though the other half remained independent and resisted any attempts at occupation. This was the situation in 976 when Basil II, a stern military leader and efficient administrator, ascended to the Byzantine throne. Opposing him was Samuel, a former Bulgarian general who co-ruled with Roman I and was not only unwilling to surrender his country but also aimed to recover lost territory, just as his adversary desired to seize what remained. Basil suffered a major defeat in 986 at the Battle of Trajan’s Gate, which had such an impact that the empire became embroiled in a civil war, allowing Samuel to reclaim nearly everything, at the expense of Serbs and Croats, and even march into Greece, taking advantage of concurrent Fatimid pressure.

The Byzantines were able to stop him in a surprising and decisive way in 996, near Corinth, at the Battle of the Spercheios River. Samuel’s army was shattered, Roman was taken prisoner, and Samuel himself barely escaped at night by pretending to be dead on the battlefield. With this, his plans to restore Bulgarian power vanished. Thus, despite the additional problem of the Muslim threat we mentioned earlier, by the early 11th century, Basil II was able to go on the offensive with Hungarian help and score another victory at Skopje, which opened the doors to Thessaly and southern Macedonia.

The Bulgarians were unable to halt this onslaught and were forced into a progressive retreat, which they tried to break at the Battle of Kreta, near Thessaloniki; this was in 1009, and they lost again. Though the Byzantines did not achieve decisive results with these victories, they were slowly but surely wearing down and exhausting the enemy.ç

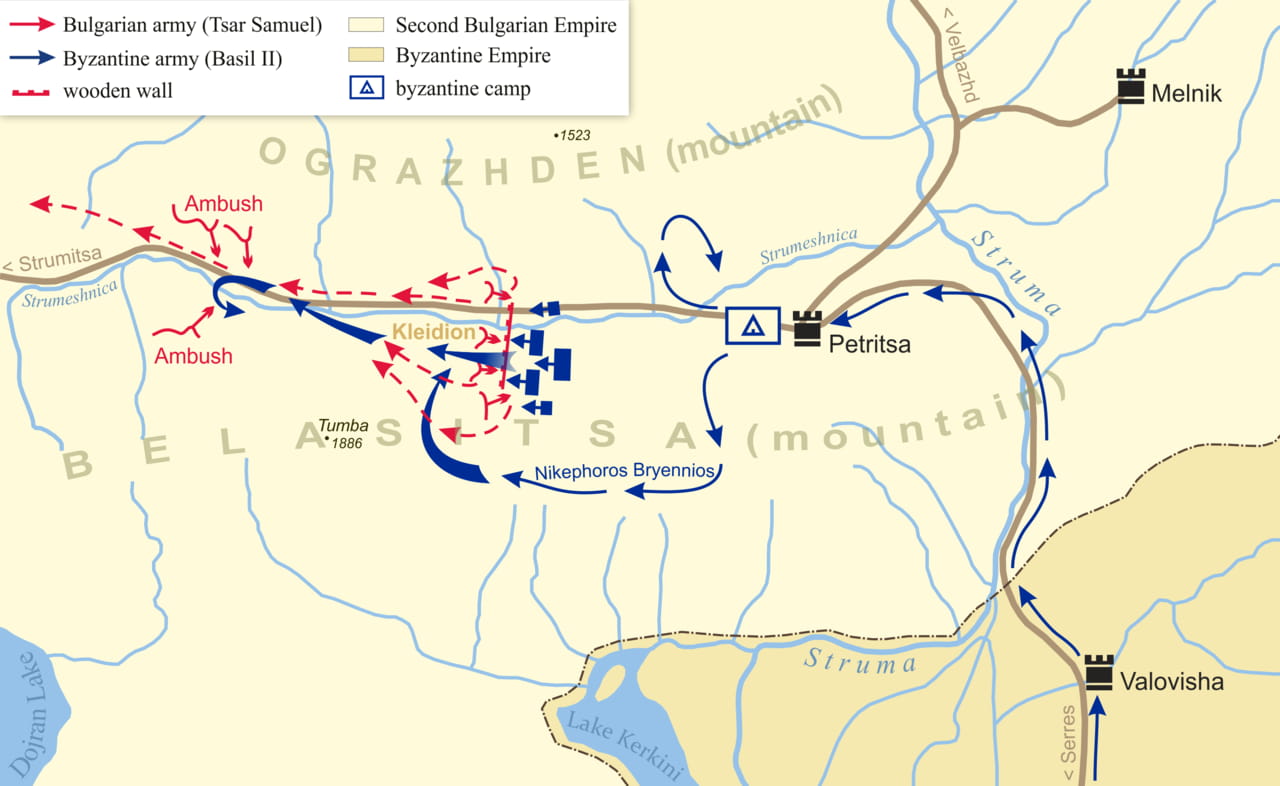

Samuel had been elected tsar after the death in 997, in a prison in Constantinople, of Roman. Of course, the Byzantines did not recognize him as such, despite having the endorsement of Pope Gregory V, since they considered that the abdication of Boris II meant that Bulgaria had ceased to exist as a state, so its successors would be nothing more than rebels. By that time, after so many defeats, Samuel also did not enjoy a strong position among his own, so in the year 1014, determined to stop the invader once and for all, he concentrated his men in the valley of the river Strimon, which was the natural passage that the Byzantine armies used to enter Bulgaria. Using the village of Kleidion (now Klyuch) as a base, he built a series of defensive systems that included moats, ditches, and a wooden wall with towers.

He managed to gather forty-five thousand men, chroniclers say with more than likely exaggeration (it is estimated that they would be half). Basil II picked up the gauntlet and set in motion a new campaign, which he entrusted to Nicephorus Xifias, governor of Philippopolis and a veteran conqueror thirteen years before of Pliska and Peslav, the ancient Bulgarian capitals. Opposing him, the local troops were led by Gabriel Radomir, son of Samuel, who successfully resisted the Byzantine attempts to force the passage. He was helped, of course, by his father’s cunning in sending an expedition led by General Nestorisa with the mission of attacking Thessalonica and thus distracting the enemy forces. However, the plan went awry when Nestorisa was finally defeated by Governor Theophylactus Botaniates, who then joined the forces fighting in Kleidion.

Now, the arrival of those reinforcements was of no use; at least not at first. Samuel’s defenses proved impregnable and seemed capable of thwarting the Byzantine objective, so it became necessary to seek an alternative. The one found is part of the classical imagery in such cases: just as the Persians did at Thermopylae and others in many similar situations, Nicephorus Xifias led his troops to surround the mountains, marching along the rugged slopes, until they surprised the Bulgarians from their rear. They suddenly had to face two fronts, allowing the main force to assault the wall, sowing chaos. A retreat was ordered to Mokrievo, but that had already turned into a save yourself if you can.

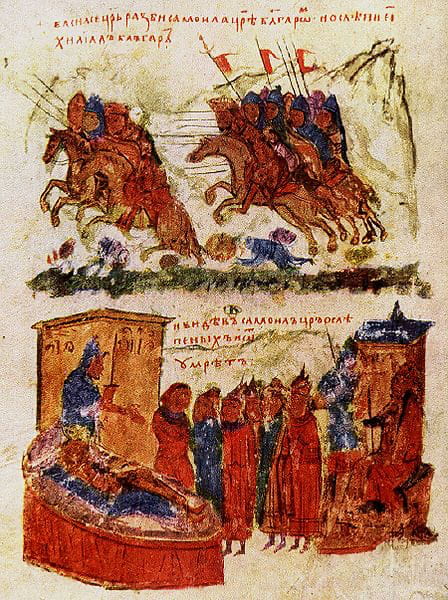

Samuel was able to escape thanks to the horse his son lent him, who stayed behind to try to reorganize the defense from the neighboring village of Strumitsa. But it was already useless, although there was still time for some notable action that would, however, bring fatal consequences. This was led by Gabriel Radomir himself against Theophylactus Botaniates, who had received the order to destroy the fortifications. He had just finished that mission and was returning to the main camp when he was ambushed by what was left of the Bulgarian force led by the imperial scion, who personally faced the other, piercing him with his lance. Basil II felt that loss deeply; so much so that, driven by anger, he ordered the prisoners to be separated into groups of one hundred and then to blind ninety-nine from each group, leaving the one remaining only one-eyed so he could guide the others. At least that is how the legend goes.

According to the sources of the time, there were about fifteen thousand captives. Current historians reduce the figure by half—assuming it were true—but it was still an impressive punishment, even though it was the usual one in those times for the seditionists. As we mentioned earlier, Basil II earned the nickname Boulgaroktonos, which means “killer of Bulgarians”. In fact, that decision was so brutal that two months later, when he saw that pathetic procession of those who were once his soldiers, Samuel suffered a heart attack and died. He was succeeded by Gabriel Radomir, who was murdered before a year had passed during a hunt—at the instigation of the Byzantines—by his cousin Ivan Vladislav, who proclaimed himself tsar only to fall dead in 1018, in the Battle of Dyrrachium, after breaking the promise of submission he had made to Basil II.

That defeat and the death of Ivan marked the definitive demoralization of the Bulgarian boyars; many, starting with Nestorisa, accepted to surrender in exchange for maintaining their titles. Thus ended the resistance, and consequently, Bulgaria became just another province of the Byzantine Empire. Although the truth is that it took barely half a century to become a second-rate power again. And indeed, Basil II, who did not marry or have known offspring, also had no successors of his stature, and the throne would pass to his brother, inferior in every way.

The application of a process of Hellenization to the Bulgarians and the abusive tax system of pronoia (which forced peasants to pay in currency instead of in kind) boosted the Bogomil movement (an ascetic Manichaean sect) and broke the tranquility again. In 1185, Bulgaria achieved its independence…until the arrival of the Ottomans.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on September 10, 2019: Cuando el emperador bizantino Basilio II mandó cegar a los miles de prisioneros que había hecho en la Batalla de Kleidon

SOURCES

Georg Ostrogosrky, Historia del estado bizantino

Franz Georg Maier, Bizancio

John Skilitzes, A synopsis of Byzantine history, 811–1057

Antonio Bravo García, Bizancio

Paul Stephenson, The legend of Basil the Bulgar-Slayer

R. J. Crampton, Historia de Bulgaria

Wikipedia, Battle of Kleidion

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.