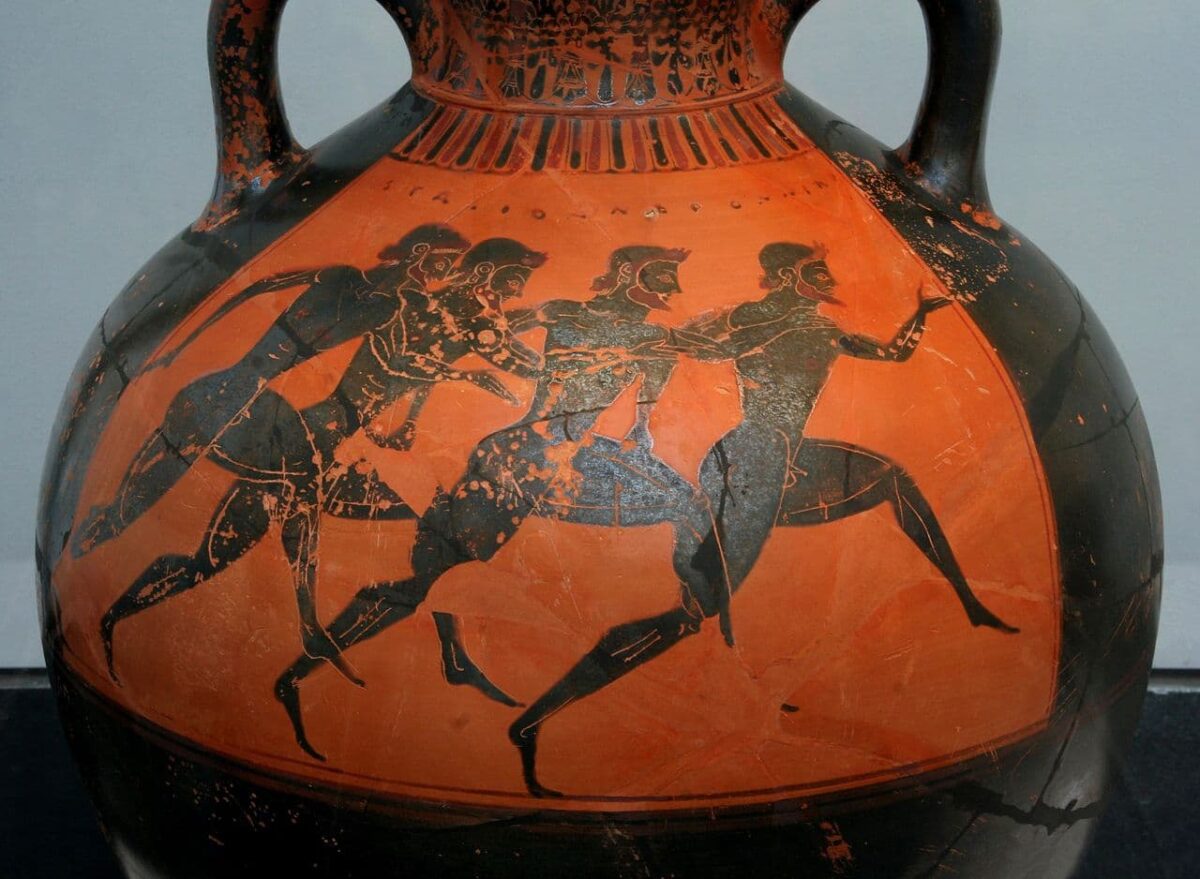

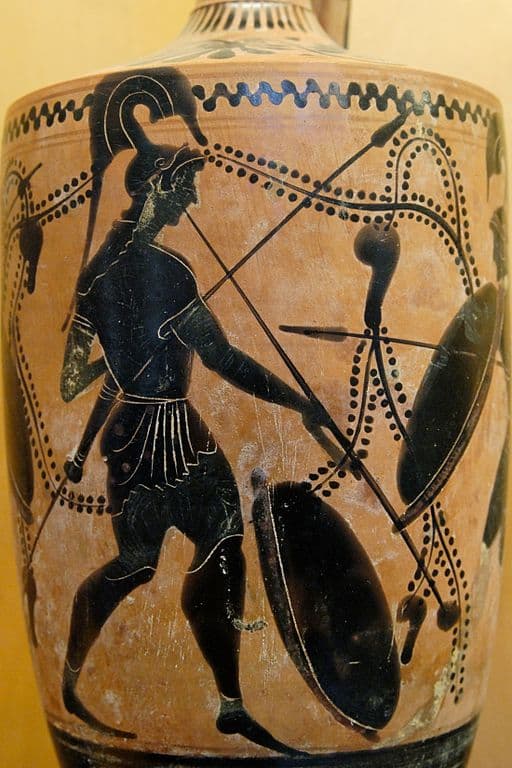

A quick glance at any artwork from Ancient Greece gives an idea of the almost religious importance of nudity, and if we interpret the images literally, how widespread its practice was in many aspects of daily life. One of these, surely the most well-known, is sports; athletes competed naked in the games from the 8th century BC, dispensing with the small perizoma (loincloth) that had been used until then. According to some—though not all—sources, this initiative came from a runner from the city of Megara named Orsippus.

Nudity is an art form invented by the Greeks in the 5th century BC, just as opera was invented in Italy in the 17th century. British art historian Kenneth McKenzie Clark, a professor and director of the National Gallery, as well as rector of the University of York, left this phrase for posterity in his work The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, published in 1956. While it is as simplistic as it is inaccurate—since nudity has existed since prehistory—it highlights the fact that the Greeks turned artistic nudity into a full-fledged iconographic expression, almost a subject in itself, closely linked to beauty.

From the time Hellenic art incorporated nudity in the 8th century BC—first in a very limited way, then more openly, paralleling the development of their civilization—nudity became an aesthetic resource that became commonplace, immortalized in statues, reliefs, paintings, and ceramics. And it was always subject to the formal canons established in each period by some of the most renowned artists, such as Polygnotus, Myron, Praxiteles, Polyclitus, or Phidias. Viewing their works—and those of others—it seems that the Greeks practically deified nudity, raising the question of whether it was equally common in real life.

The everyday life scenes, battle depictions, and representations of customs reflected in so many pieces, thematically distant from literature or mythology, lead one to believe it was. Perhaps the best example is physical activities, which were practiced without clothing to the point where they may constitute the quintessential model. The question is: When did athletes begin competing naked? Tradition gives us a specific answer: 720 BC, with a notable name: Orsippus of Megara. In his Description of Greece, the geographer and historian Pausanias provides a citation on the matter:

Orsippus, who won a race in the stadium at Olympia running naked, when athletes used to wear a loincloth, is buried near Coroebus. They say that later Orsippus became a general and seized a part of the neighboring country. I believe he purposely let his belt drop because he knew a naked man runs faster than one who is belted.

We don’t have much information about Orsippus. We know he was born in the 8th century BC in Megara, a city located on the outskirts of the Attica region, on the coast of the Gulf of Aegina, facing the island of Salamis. At that time, Megara was experiencing a period of commercial and cultural prosperity (it was home to a philosophical school founded by Euclid and the birthplace of the lyric poet Theognis), which eventually led it to rival Athens and Corinth; it began to decline after the Peloponnesian War, somewhat paradoxically, as it had sided with the victor, Sparta. Saint Jerome records a famous saying about the inhabitants of that city: They build as if they were to live forever; they live as if they were to die tomorrow.

The origins of Megara date back to the Neolithic, though the city itself was likely founded by the Dorians, who displaced older populations of Ionians and Boeotians in various waves. The Megarians quickly came into conflict with their neighbors, the Corinthians and Athenians, contesting the former for border territories and the latter for the island of Salamis (Megara became a naval power, contributing twenty triremes to the Greek side in the Battle of Salamis during the Persian Wars and land forces at the Battle of Plataea).

Thus, it can be inferred that such a thriving place also excelled in sports, and indeed, Megara had great champions in the stadion or foot race, which was the most prestigious event to the point where its winner was considered the overall victor of the Olympic Games (which at that time lasted only five days). One of these champions was Menon, who won in the 19th Olympiad (704 BC); another was Kratinus, who triumphed in the 32nd Olympiad (652 BC) while his brother Kromaios won in boxing; and a third, Democritus, won after a long dry spell in the 152nd Olympiad (172 BC).

According to Athenaeus of Naucratis in his Deipnosophistae, another prominent Megarian in this regard was Herodorus, a musician who, between 328 B.C. and 292 B.C., won ten times in a different and unusual event, the championship of the kerykes (heralds) and salpinktai (a type of trumpet). The kerykes were responsible for ritually announcing the competitions, and in the 96th edition of the Olympic Games (396 B.C.), their specialty was added to the list of events, with the judges awarding victory to the one who demonstrated the best enunciation while speaking and the strongest breath while blowing the salpinx.

Using Amarantus of Alexandria as a source, Athenaeus mentions that Herodorus was three and a half cubits tall, equivalent to about one meter sixty, but he consumed large amounts of bread, meat, and wine, which gave him extraordinary strength and lung capacity, allowing him to play two instruments at once. We note Herodorus because he also had the chance to apply these talents in war: in 303 B.C., he participated in the siege of Argos by Demetrius I, encouraging soldiers with his musical sounds. In this versatility, he resembled the earlier Megarian we’re discussing, Orsippus.

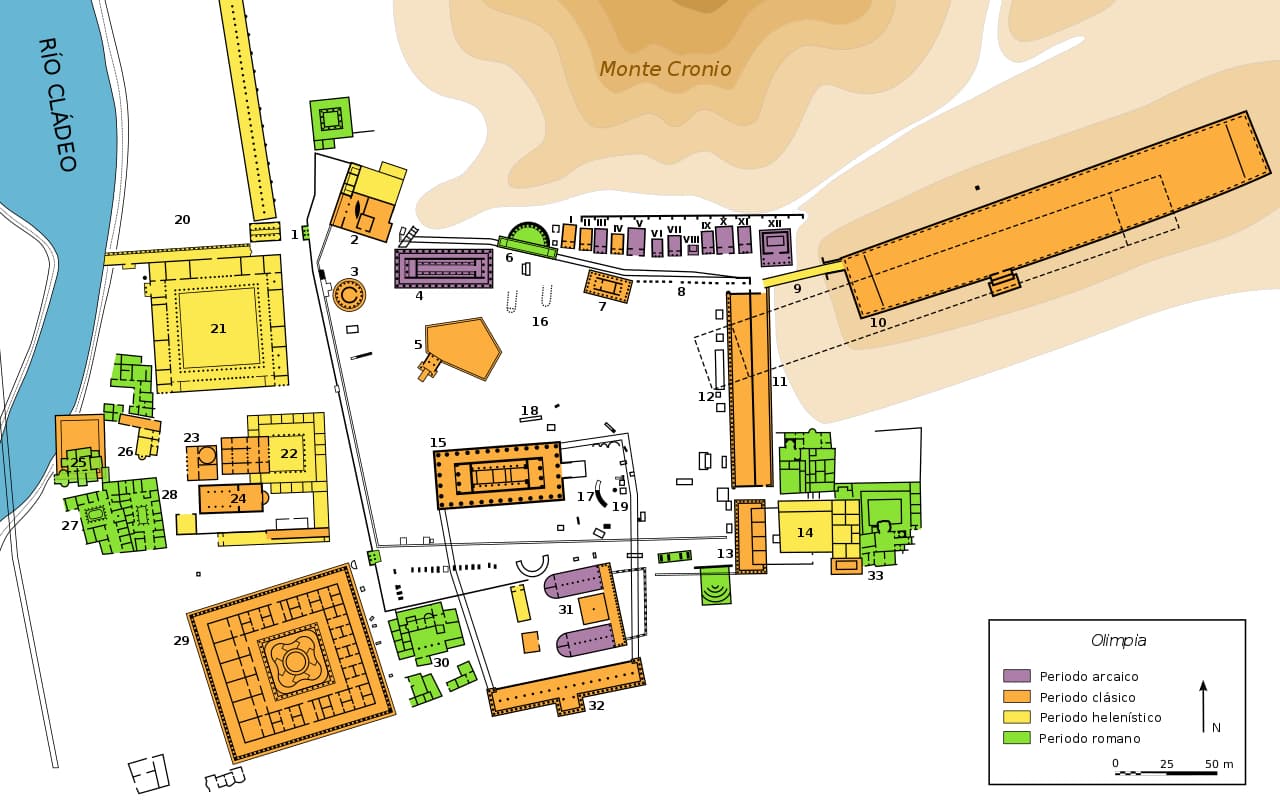

Orsippus, as Pausanias notes, was a general in the wars Megara fought against the Corinthians. However, that’s not what made him famous in history, but rather the fact that he won a race at the Olympic Games running completely naked. Specifically, in the 15th edition, held in 720 B.C., in the stadion race, which took place in the Olympic stadium. It was the most prestigious event, consisting of running approximately 183 meters (equivalent to 600 times the length of Heracles’ foot).

The race began with a trumpet blast signaling the spectators to remain silent, as the heralds began announcing the names of the athletes, their fathers, and their respective hometowns. A judge was responsible for starting the race, using a formula similar to the current one: first ordering the athletes to line up «πόδα παρὰ πόδα», meaning “foot to foot” (the afesis, or starting line, wasn’t painted—with lime—until the 5th century), then shouting «¡ἔτοιμοι!» (“Ready!”) and finally starting the race with the word «¡ἅπιτε!» (“Go!”). In Olympia, it was a straight course from the stadium to the temple of Zeus, where the terma (finish line) was located.

As we said, Orsippus won it in 720 B.C. and did so running naked. Some sources, like Dionysius of Halicarnassus (a Greek historian and rhetorician of the 1st century B.C.) in his work Roman Antiquities, Sextus Julius Africanus (a historian and Hellenistic apologist, considered the father of Christian chronology) in his Chronographia, or Pausanias himself, say that he wasn’t actually the first to do so. Acanthus of Sparta, an athlete who won two victories—one in the diaulos (a double-length race equivalent to 384.54 meters) and another in the dolichos (a foot race of variable length, ranging from seven to twenty-four stadiums)—preceded him.

They base this claim on Thucydides, who in his History of the Peloponnesian War asserts that the Lacedaemonians were the first to run naked in the games, though he doesn’t explicitly mention Acanthus. In any case, Acanthus would not have undressed voluntarily, but rather lost his loincloth during the race (and, hindered by this, lost the race). Thus, Orsippus seems to have retained that honor. What’s curious is that it’s not known why he decided to forego the usual perizoma. It’s possible that it also fell off by accident during the race or that he deliberately discarded it.

The reason? Perhaps he felt more comfortable without clothes, whether for freedom of movement or because of the heat. Regarding the latter, it’s worth noting that the Olympic Games were held in the months of Apollonius and Parthebius, corresponding to July and August, when temperatures in Greece could reach scorching levels. Philostratus of Athens vividly describes how everything was «subject to the searing rays of Helios», while Lucian of Samosata speaks of the «hot, crowded masses of people» as they entered the Olympia stadium.

Whatever the case, Orsippus received his olive crown, a prize that had been awarded since 752 B.C. (a boy whose parents were both alive would cut as many olive branches as there were winning athletes, using a golden knife, from a tree known as Kalistephanos), and his example led to all subsequent athletes competing naked.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on October 21, 2024: Orsipo de Mégara, el primer atleta que participó desnudo en los Juegos Olímpicos

SOURCES

Pausanias, Descripción de Grecia

Dionisio de Halicarnaso, Historia antigua de Roma

Ateneo de Náucratis, Banquete de los eruditos

Tucídides, Historia de la Guerra del Peloponeso

Miguel Ángel Delgado Noguera, Los Juegos Olímpicos ayer y hoy. 1971-72

Kenneth McKenzie Klark, The nude. A study in ideal form

Stephen G. Miller, Ancient Greek athletics

Wikipedia, Orsipo

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.