On October 31, 2009, an elderly man, nearly a century old, passed away in Beijing. His name was Qian Xuesen, and in China, he is considered a national hero for being the father of the country’s astronautics program, to the point that China’s first manned space mission, successfully carried out in 2003, was based on his scientific work. It was a nearly final satisfaction for him because he had started his career in the U.S. but was expelled after being accused of sympathizing with communism during the McCarthy-led persecution period.

Qian was born in Hangzhou in late 1911, although he left the city at barely three years old because his father, a Ministry of Education official, was transferred to Beijing. The young Qian grew up in the capital until 1934, when he went to the National Chiao Tung University (now Jiatong University in Shanghai) to study mechanical engineering.

He then did his military service at the Nanchang Laoyingfang Air Base (now a joint civil-military airport), and after completing it, he received a Boxer Indemnity Scholarship, a type of scholarship the U.S. offered to Chinese students to appease anti-American sentiment following the international intervention against the Boxer Rebellion.

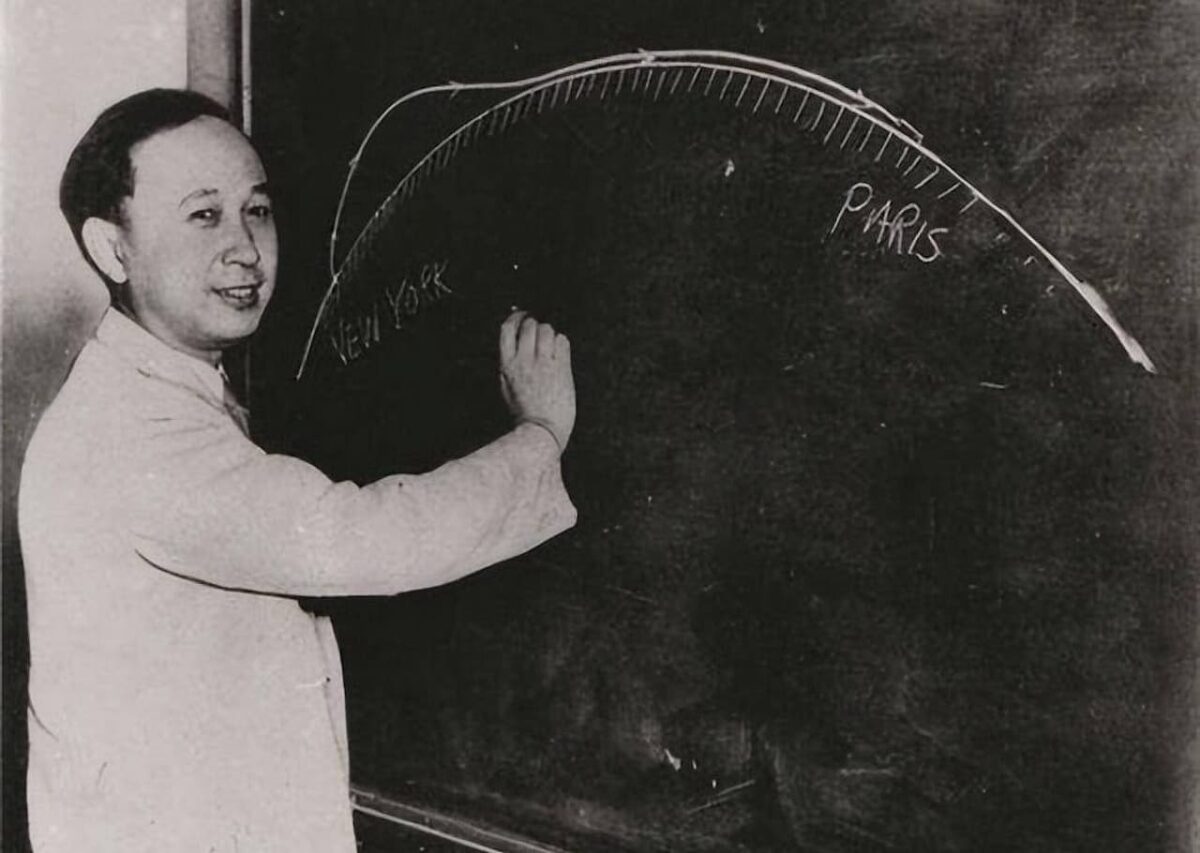

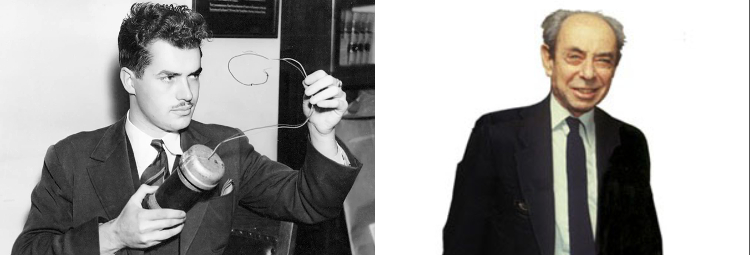

Qian’s scholarship brought him to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he earned a Master of Science degree the following year. He then formed friendships with some professors, admiring the experimental approach to their research compared to the theoretical one dominant in China, just as they recognized his exceptional intellect. One of those professors was Theodore von Kármán, a Hungarian-born mathematician, physicist, and engineer specializing in aeronautics, who had designed one of the first helicopters and, after emigrating to the U.S. in the 1930s, led the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory at another major technological institute, the California Institute of Technology. In fact, Kármán convinced his protégé to join him in this new phase.

It was 1936, and they focused their experiments on rocket development, a line of research that caused more than a few scares on campus, which is why they were nicknamed the “Suicide Squad”. Qian, or Hsue-Shen Tsien, as he was known at the time, earned his doctorate in 1939, just as World War II began. In 1942, he joined the Manhattan Project, the U.S. plan to develop an atomic bomb, with the temporary rank of colonel.

However, Qian worked on a complementary program called the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which focused on developing missiles similar to the German V-2s. The prototype was named Private A, which flew in 1944, followed by other models like the MGM-5 Corporal (the first designed to carry a nuclear warhead) and the WAC Corporal.

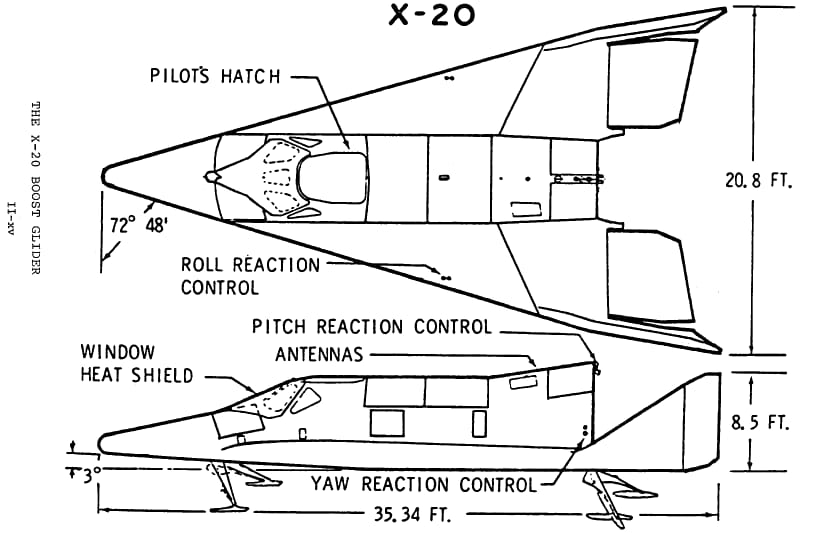

Qian also worked on the design of an intercontinental spaceplane, which would later form the basis for the X-20 Dyna-Soar. This was a craft capable of aerial reconnaissance and bombing but also of flying into space to maintain satellites in orbit or, more importantly, sabotage those of enemy powers. Boeing proposed it in 1957, but it was canceled that same year as the space race began. However, the X-20 Dyna-Soar and Qian’s design would later materialize in the Space Shuttle.

Exactly ten years before that Boeing project, Qian married Jiang Ying, an opera singer and music professor born in Haining to a Chinese-Japanese family. She was the daughter of Jiang Baili, one of Chiang Kai-Shek’s generals, and had studied in Berlin. When the war broke out, she moved to Switzerland, studying singing at the Musikhochschule in Lucerne in 1944 before returning to China and then moving to the U.S. in 1947.

Permanently, or so they thought, as their two children were born in the U.S., even though Jiang and Qian married in Shanghai. He had been offered a teaching position at the aforementioned Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and two years later, through von Kármán, he moved to the California Institute of Technology. In 1949, he applied for citizenship, according to some accounts, although there is no official record, and his wife always denied that he had applied.

The uncertainty around this is part of the context of the first accusations against Qian. Intelligence services suspected him due to his frequent travels to China, but no action was taken until 1950, just before the Korean War began, when he was interrogated by the FBI, and his security clearance was revoked. McCarthyism was just starting, with its paranoia about a communist conspiracy in the country, opening the door to the infamous witch hunts. Several scientists involved in nuclear programs were convicted, such as chemist Harry Gold, engineer Morton Sobell, British physicist Klaus Fuchs, and David Greenglass (who struck a deal at the cost of accusing his sister Ethel and her husband Julius Rosenberg, both of whom were executed).

Many of those affected in different spheres were probably just progressives, but Cold War winds were blowing. In short, seeing the situation, Qian decided to leave. He was preparing to move when the company he hired for the job reported him after seeing some documents marked as confidential. The Immigration Service arrested him, and he argued that they were very old files and that the officials had confused mathematical notes with secret formulas. It was later proven that the material was not classified, but other factors had already contributed to putting him in the spotlight.

For example, the fact that during his stay in California, he attended meetings with Frank Oppenheimer (Robert’s brother), Jack Parsons, Frank Malina, and Sidney Weinbaum, a group of scientists who formed the so-called Unit 122 of the Communist Party of Pasadena and had also been arrested. The first two made a deal to avoid prison in exchange for testifying against Weinbaum and Qian. They were spared, although they had to give up their careers. However, things went worse for those they informed on: Weinbaum was sentenced to four years in prison for perjury (he had claimed to have nothing to do with communism), and Qian, who claimed in vain that these were only social gatherings with no political background, was confined to Terminal Island, a low-security federal prison in Los Angeles.

He spent a couple of weeks there while he was investigated. It was discovered that when he returned from China in 1947, his response on the entry form was that he had never been part of an organization hostile to the U.S. government, even though his name and details appeared on a 1938 file of the American Communist Party. He replied that he was loyal to the Chinese people and refused to admit that the U.S. government had the right to force him to choose between the Chinese and the Americans in a hypothetical conflict. This echoed words he had once said to Dan A. Kimball, Under Secretary of the Navy and his friend (who always refused to believe he was a communist), expressing that he didn’t want to contribute to making weapons that could be used against his fellow Asians.

This was the last straw. In the spring of 1951, he was placed under house arrest and forbidden to leave Los Angeles. Since he could only teach unclassified subjects, he used that time to write Engineering Cybernetics, his first book, which wouldn’t be published until three years later. By then, China had already protested his situation, and for five years, diplomatic negotiations took place between the two countries. In the summer of 1955, he was finally authorized to travel and boarded the ship SS President Cleveland with his family, bound for Hong Kong. Rumor had it that this was part of an exchange in which China returned eleven airmen it had held as prisoners since the Korean War.

The Chinese welcomed Qian as a prodigal son. In 1957, he not only joined the Academy of Sciences but was also named director of the so-called Fifth Academy, the seed of what is now the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC). It was the body responsible for developing ballistic missile and atomic weapons programs, so the Dong Feng (East Wind) series owes much of its creation to him, as does the first atomic device successfully detonated (1964) and the first hydrogen bomb (1967). He also played a significant role in the space rockets that China began focusing on in the 1970s, the Chang Zheng (Long March). Another unexpected consequence of Qian’s exile was the triumph Mao claimed by receiving him, strengthening his position to initiate the Great Leap Forward.

In the following decades, Qian carried out extensive research and teaching, not only in his field but also in many others, including medicine, the humanities, and qigong (a type of martial art based on controlled movements and meditation, similar to tai chi). In 1979, the California Institute of Technology, where he had worked, awarded him the Distinguished Alumni Award, and in 1991, it even returned his old research documents. The American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics also invited him to visit the U.S., but he was still bitter about how he had been treated and refused to go without an official apology from the government, which never came.

By that time, he was already retired, and his health began to deteriorate, forcing him to enter the hospital. From there, in 2003, he witnessed China’s crowning achievement in the space race when it sent its first astronaut, Yang Liwei, into orbit aboard the Shenzhou spacecraft; a Chang Zheng 2F rocket, one of those Qian had helped design, was used for the launch, so we can imagine the satisfaction he felt at that moment. Afterward, he received numerous honors and accolades, both national and international (including having an asteroid named after him), until his death in 2009 at the age of ninety-seven.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on September 12, 2019: Qian Xuesen, el científico expulsado de Estados Unidos que metió a China en la carrera espacial

SOURCES

Iris Chang, Thread of the Silkworm

Tianyu Fang, The man who took China to space

Milton Viorst, The bitter tea of Dr. Tsien

Brian Harvey, China’s space program. From conception to manned spaceflight

Franklin O’Donnell, JPL 101

Wikipedia, Qian Xuesen

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.