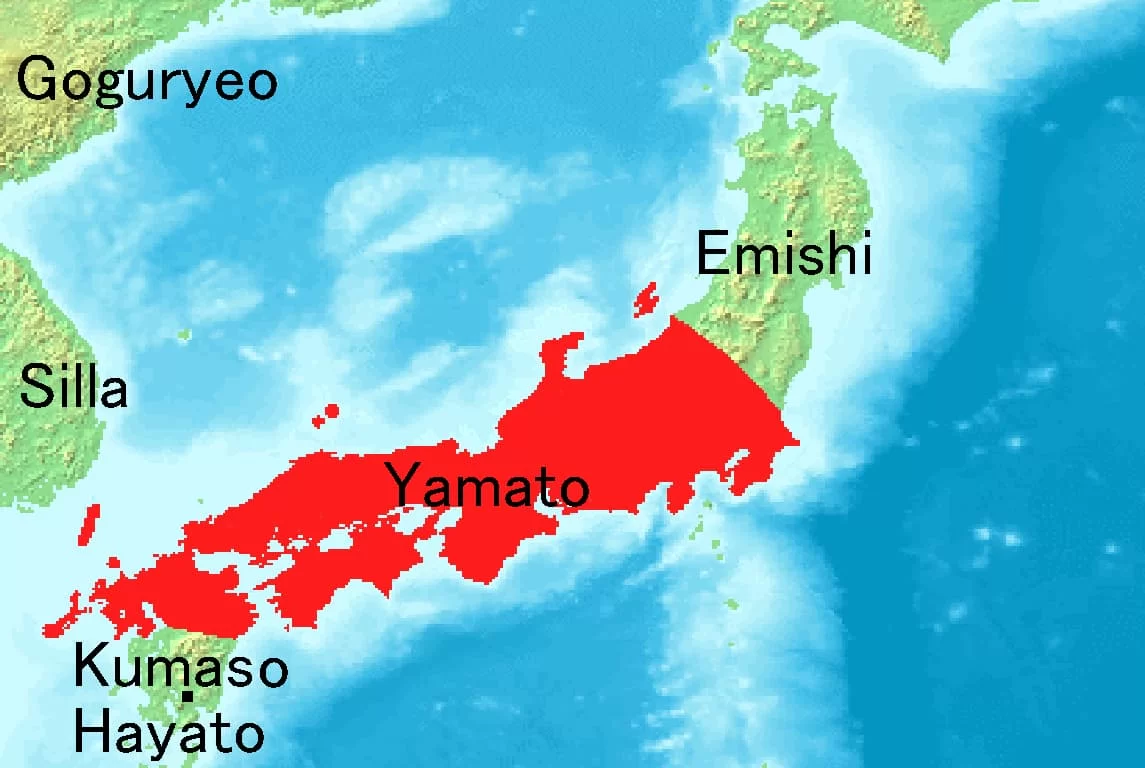

If we were to ask what is the world’s oldest active monarchy, most readers would probably say the British without giving it much thought. That would be an incorrect answer. We need to shift the focus to the Far East because that is where Japan is, whose kōshitsu, or Imperial House, has been at the helm of the country for over two and a half millennia. It doesn’t have an official name, but it’s informally known as the Yamato Dynasty, referring to the Yamato Ōken, a tribal alliance from the eponymous region formed in the 4th century AD among the leading noble families of central and western Japan. This alliance also gives its name to a period in ancient Japanese history.

The Records of the Three Kingdoms, a Chinese work from the late 3rd century AD, was the first to record the word Yamatai (or Yamatai-koku, meaning “Yamatai country”) to refer to the domains of Himiko, a shaman queen who lived in the area of present-day Japan. The first known name for this territory was Wa (a derogatory term meaning “dwarf,” stemming from the common stereotype among the Chinese and Koreans that the Japanese were of small stature), corresponding to the Yayoi period (from the Neolithic to the end of the Iron Age), followed by the Jōmon period (which lasted until approximately 300 BC).

No one knows exactly what region Yamatai referred to; there’s not even certainty that the term is related to Yamato, the area now part of Naru Prefecture. In any case, after Queen Himiko’s death, an unknown king briefly took her place, followed by Queen Toyo (also called Iyo), whom some historians believe to be the mother of Sujin, listed as the 10th emperor in traditional records, although some researchers consider him legendary and identify him with the first emperor, Jimmu, to whom Sujin’s biographical details might have been transferred. In any event, Yamatai disappeared from historical records after that.

As mentioned earlier, a century later the Yamato Ōken or Yamato Royalty emerged, centered in the Nara region at a time when the Japanese archipelago was not yet unified and various power centers existed. To secure their position against others, the Yamato agreed to vassalage with the Chinese Jin Eastern and Liu Song dynasties, while also maintaining diplomatic relations with the Korean kingdoms of Baekje and Gaya. The dates are unclear, as is the information, which comes exclusively from Chinese sources.

One theory argues for the coexistence of two simultaneous dynasties, the Yamataikoku in Kyushu and the Yamato kingdom in the Kinai region, though another theory suggests there were more. In any case, this marked the start of the Kofun period, which lasted until the 7th century, followed by the Asuka period (538-711). During these times, we can already speak of established dynasties, with four powerful successive okimi or rulers: Seinei, Kenzo, Ninken, and Buretsu, who began to break China’s influence. Focused on internal governance, these dynasties often went to war, as seen with the Keitai and Kinmei, in efforts to achieve unification.

Yamato royalty was still culturally sustained with the introduction of elements brought from China, such as the calendar or Buddhism, but by the end of the period, the system collapsed due to conflict between the Soga and Mononobe clans, the former Shintoist and the latter Buddhist. This conflict resulted in the proclamation of Prince Shotoku and Empress Suiko, who undertook a deep reform from which the so-called Ritsuryō State emerged. After Suiko’s death, a second reform, known as Taika no Kaishin, took place, and by 701 the name Japan began to be used in writing (although still pronounced “Yamato”), and the title of ruler shifted from okimi to tenno (emperor).

As mentioned earlier, Sujin was one of the first fourteen emperors according to tradition; all of them, up to Chuai, are considered legendary, although Sujin shows some signs of historicity. Some extend the dubious list to the fourteen emperors of the Kofun period, making Kinmei, from the Asuka period in 509 AD, the first proper emperor. From him onward, there were 101 more emperors, spanning the Asuka, Nara, Heian (during which the Fujiwara clan began manipulating imperial power as sessho—regent—which would eventually lead to the shogunate), Kamakura, Nambokucho, and Edo periods, continuing into modern times (the time of the Meiji Restoration), with five more emperors, including the current one, Naruhito. The timeline stretches from 711 BC (if we accept the legendary figures) to today.

Therefore, the Imperial House of Japan is the oldest continuous hereditary monarchy in existence. According to its constitution, it constitutes “the symbol of the State and the unity of the people,” and although it is commonly referred to as the Yamato House, it actually has no surname. Each of its members gives their name to their reign; for example, Mutsuhito is remembered as Meiji, and Hirohito as Showa. The head of the Imperial House is, of course, the tennō (emperor), and the imperial family includes the kōgō (empress), the jōkō (emeritus emperor), the kōtaishi (crown prince), the shinnō (princes), the naishinnō (princesses), and various other relatives.

Since 1947, when eleven shinnōke (branches of the family) were forced by the Rengōkokugun saikōshireikan (Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, General MacArthur at the time) to renounce their succession rights and women were excluded from the line of succession—updating a legal provision from 1889—the imperial family has been limited to the male descendants of Emperor Yoshihito, the son of the famous Mutsuhito and the father of the equally renowned Hirohito. This is why Hirohito was succeeded by his eldest son, Akihito, and after his abdication, by his own eldest son, Naruhito. However, Naruhito has only one daughter, Princess Aiko, so the first in line to the throne would be the emperor’s brother, Fumihito, Prince Akashino.

In 2005, the Japanese government considered a change to allow Aiko to reign, but it was put on hold the following year when Fumihito had a son, Prince Hisahito, who is now third in the line of succession after Fumihito and Hisahito. This complex situation arises from the exclusion of women (despite the fact that eight women have reigned, the last being Go-Sakuramachi, between 1740 and 1813). Princesses lose their titles when they marry someone outside the imperial family, which is why it now consists of only seventeen people. This reflects the tradition before the Meiji period and is confirmed by Chapter 1 of the Constitution of Japan and by the Kōshitsu Tenpan or Imperial Household Law.

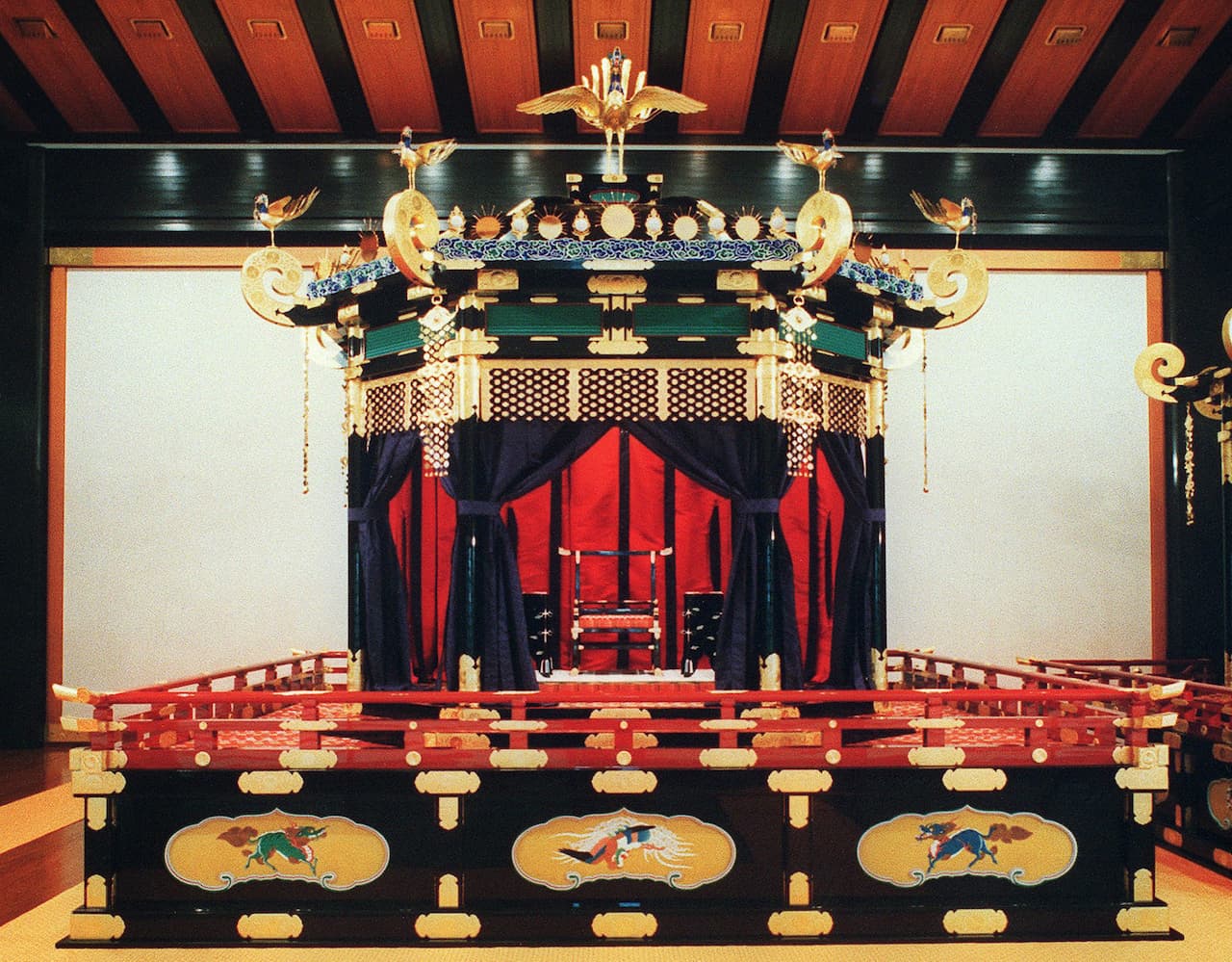

Some of those collateral branches have disappeared, and today five remain, forming the Kyū-Miyake or Old Imperial Family; they are the Fushimi, Asaka, Higashikuni, Kaya, Kuni, and Takeda. However, they are not part of the kōshitsu and, consequently, have no chance of occupying the Chrysanthemum Throne, a name given to the imperial throne because the chrysanthemum is the national flower and forms the emperor’s coat of arms. The term “Chrysanthemum Throne” is also used as a synonym for the Japanese monarchy, in a similar way that the term “Crown” (or even the word “Throne”) is used in the West.

The emperor has a purely representative role as head of state without political powers. However, like the king of England is the head of the Anglican Church, the emperor is the high priest of Shintō (“Way of the Gods”), Shintoism, the native religion of the country, which in the Middle Ages merged somewhat with Buddhism (hence, the emperor does not have freedom of religion). After Japan’s defeat in World War II, Hirohito formally renounced the tradition of being considered divine, a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu Okami. Hirohito’s role—whose reign is known as Shōwa because it is customary to name it after the emperor’s death—in the war was highly controversial, but he wasn’t the only one.

Others, such as Princes Higashikuni Naruhiko (Hirohito’s uncle and prime minister), Yasuhito Chichibu (Hirohito’s younger brother and army general), Takahito (another brother and cavalry officer), and Tsuneyoshi, were accused of indirectly participating (by authorizing, financing, and providing means) in human experiments conducted by the infamous Unit 731, though MacArthur exonerated them. This past is partly why the imperial family stopped visiting the Yasukuni Shrine, a place of worship for Japanese war dead that includes those convicted and executed for war crimes.

Despite these controversial points, the majority of Japanese people support the parliamentary monarchy. In 2016, its budget was estimated at six billion one hundred million yen, primarily used to pay employees: there are nearly a thousand of them due to the strict protocol, which prevents any worker from performing multiple duties. This includes butlers (nearly fifty per family member), gardeners, plumbers, electricians, doctors (there are always four on call), priests, stable boys, musicians (there is a gagaku orchestra, traditional music), silk worm breeders, chauffeurs, and even about thirty archaeologists tasked with maintaining royal tombs.

Some of the budget also goes to finance a small clinic, a well-stocked wine cellar, farming estates, the Kouguu-Keisatsu Hombu (Imperial Guard Headquarters, which has 900 members), and the vehicle fleet, as well as the salaries assigned to each royal family member (they are not allowed to hold other jobs). Interestingly, during trips, there is a limit of 110 pounds per person per night. These funds come from the state because, although the Japanese monarchy was one of the richest in the world until World War II, there was no distinction between the crown’s properties and those of the emperor personally. Afterward, they were separated.

Many palaces and lands were donated or sold, becoming state property, and the staff was reduced to a sixth of its original size. Even so, Hirohito’s will recorded a fortune of eleven million pounds sterling in 1989; his son’s assets were estimated at forty million dollars in 2017. The palaces of Kōkyo (in Tokyo) and Kyōto Gosho (in Kyoto), as well as other properties (villas, mansions, farms, hunting grounds, residences, etc.), belong to the state. This privileged economic status is just another factor that separates the imperial family—who in fact are not listed in the civil registry—from ordinary citizens.

Members of the Imperial House and ordinary citizens never interact personally or via phone or the internet. If a family member places an order by mail—they cannot visit stores—they must use an employee’s name. Their activities are monitored around the clock, and even their food is controlled; palace chefs are instructed not to exceed 1,800 calories per meal. The menus typically combine native and Western food, and according to rumors, no Chinese dishes are ever prepared.

The Jijū-shoku (Board of Chamberlains), an internal department of the Imperial Household Agency (the administrative body managing the monarchy), handles matters related to the emperor, the empress, and their unmarried children, as well as the emeritus emperor and his consort. In the past, up until 1945, their duties included such minute details as deciding the appropriate attire—traditional, military, or civilian—for the emperor and his relatives on various occasions.

Another important institution is the Kōshitsu Kaigi (Imperial House Council), created in 1947 and made up of ten people, headed by the prime minister, to deal with matters like family marriages, loss of status, changes in succession, and regency. Currently, the Chrysanthemum Throne is occupied by Naruhito, who succeeded his father Akihito after the latter’s abdication. His reign, alongside his wife Masako, is known as the Reiwa era—the name he will be given posthumously—following his father’s Heisei era.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on October 14, 2024: La dinastía reinante más antigua del mundo es la Casa Imperial de Japón, descendiente de una reina chamán

SOURCES

Michiko Tanaka (coord.), Historia mínima de Japón

Ben-Ami Shillony (ed.), The emperors of Modern Japan

Brett L. Walker, Historia de Japón

Ben-Ami Shillony, Enigma of the emperors. Sacred subservience in Japanese history

Agencia de la Casa Imperial de Japón

Wikipedia, Familia Imperial Japonesa

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.