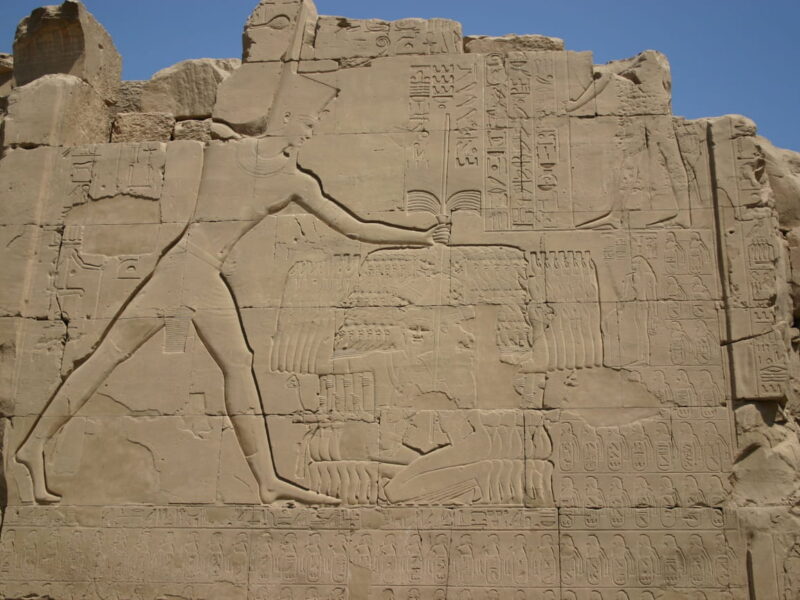

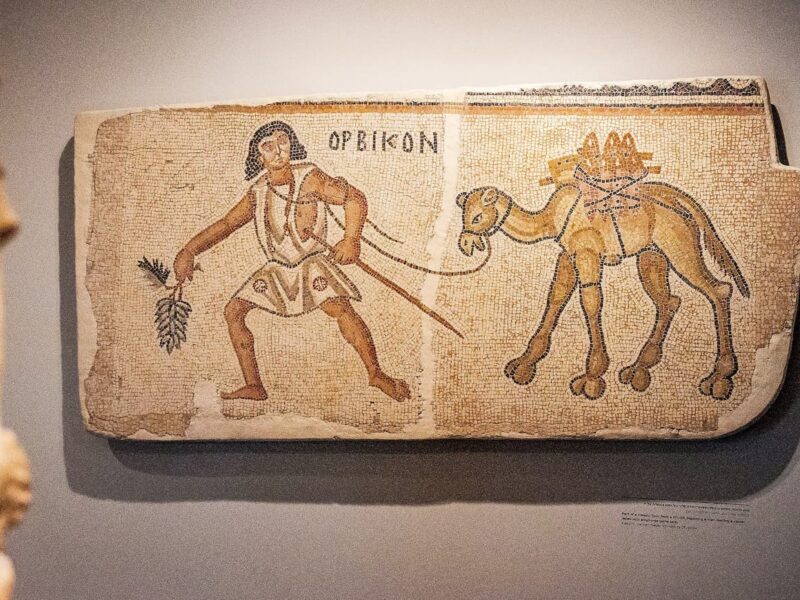

For centuries, children in Ancient Egypt learned to read using a text known as The Satire of the Trades, a document dating back to around 2400 BCE.

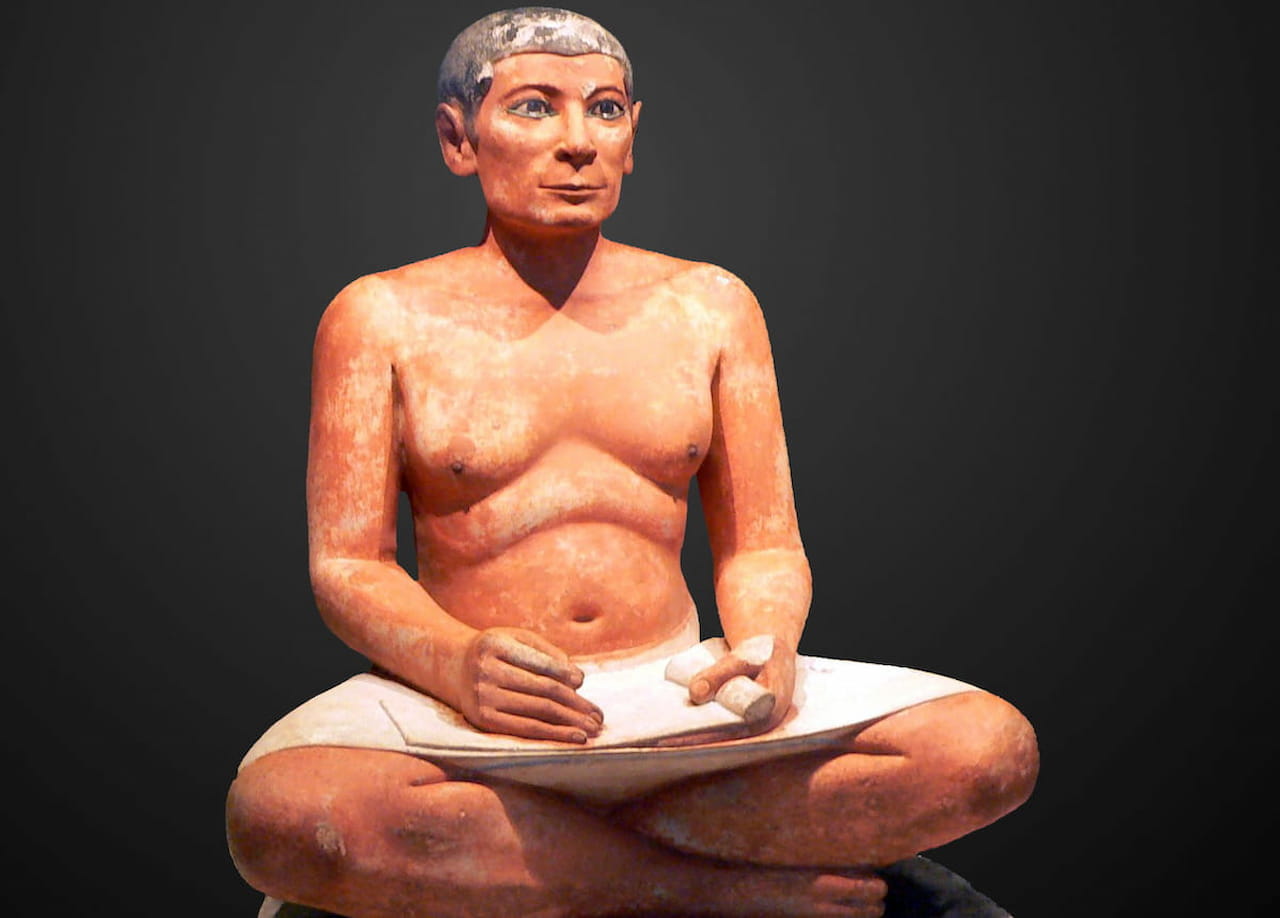

This educational text presents advice from a father to his son, encouraging him to pursue the profession of a scribe by describing the physically demanding nature of various other professions. The aim of the text was to persuade students that becoming a scribe was the most esteemed career, offering a life of relative comfort and respect.

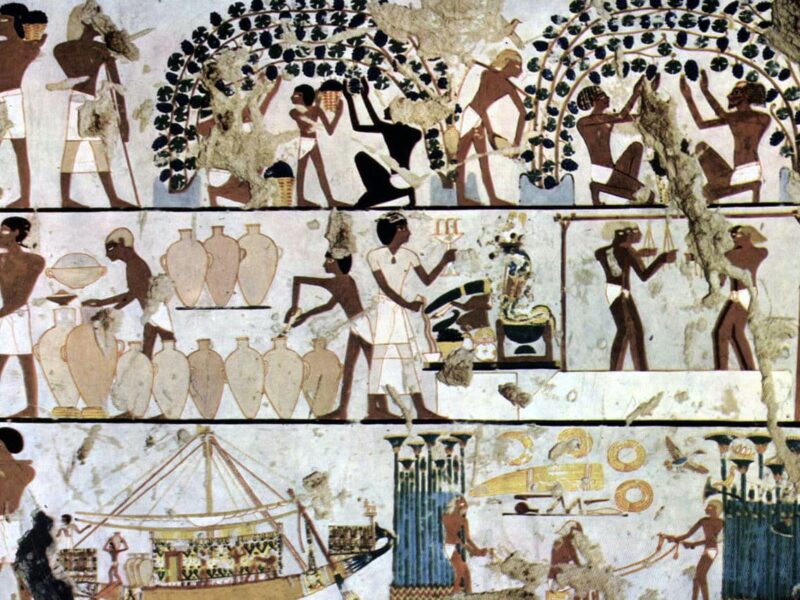

In The Satire of the Trades, also referred to as The Instructions of Dua-Kheti, a father takes his son to school and, along the way, vividly describes the challenges faced by other workers, such as farmers, carpenters, and fishermen. He underscores the hardships these laborers endure, emphasizing their physical strain and lower social status.

The peasant spends all day lamenting, his voice as hoarse as the cawing of a crow. His fingers and arms ooze and stink excessively. He is worn out from being in the mud, rags and rags are his clothes. He is as bad as one who is among lions: sick, he must lie down on the marshy ground. When he leaves the camp and arrives home late in the evening, he is completely exhausted by the march.

The Satire of the Trades

In contrast, he presents the life of a scribe as privileged, with intellectual pursuits bringing recognition and an easier lifestyle. He exclaims:

It is the best of professions. There is nothing like it in the whole country. Dedicate yourselves body and soul to books! There is nothing better than books! Look, there is no profession without a boss. Except that of a scribe. He’s the boss.

The Satire of the Trades

Judith Jurjens, a doctoral researcher, has studied the educational methods of Ancient Egypt, focusing on how The Satire of the Trades was used in practice. According to her research, the text was central to the curriculum for nearly a thousand years.

Even though the language of the text was centuries old by the time it was used, children still learned to read and write by memorizing and copying it, much as students today study classical works like Shakespeare.

Jurjens explains that the widespread use of the text is evident because numerous copies of it have been found, many riddled with mistakes. These errors indicate that students were struggling with the antiquated language and unfamiliar contexts of the professions described. She points out that these texts were as distant from the lives of young Egyptians as Elizabethan English might be for today’s readers.

The actual classroom practices of Ancient Egypt, however, have been less clear. Through her research, Jurjens examined nearly a hundred sources, many of which had been previously overlooked. These sources reveal fascinating details about the teaching methods. For example, students often included the date on their work, which suggests that lessons did not follow a fixed schedule—there might be a gap of days or even weeks between sessions, with no formal weekend breaks.

Jurjens also discovered that while it was previously known that teachers would write out literary texts for students to copy, some new evidence shows a different approach. In one case, a teacher would write the first part of a passage from The Satire of the Trades and then ask the student to complete the rest from memory. The differences between the teacher’s elegant handwriting and the student’s uneven scrawl reveal the difficulties faced by young learners.

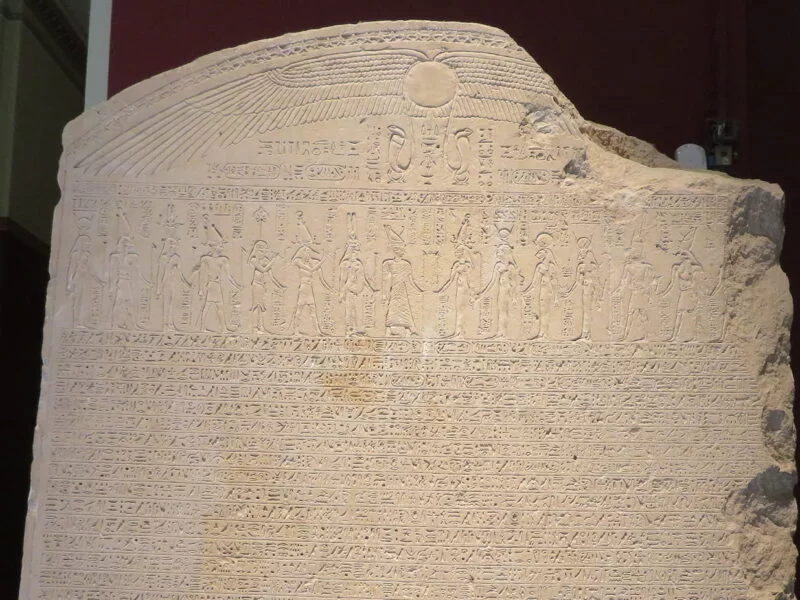

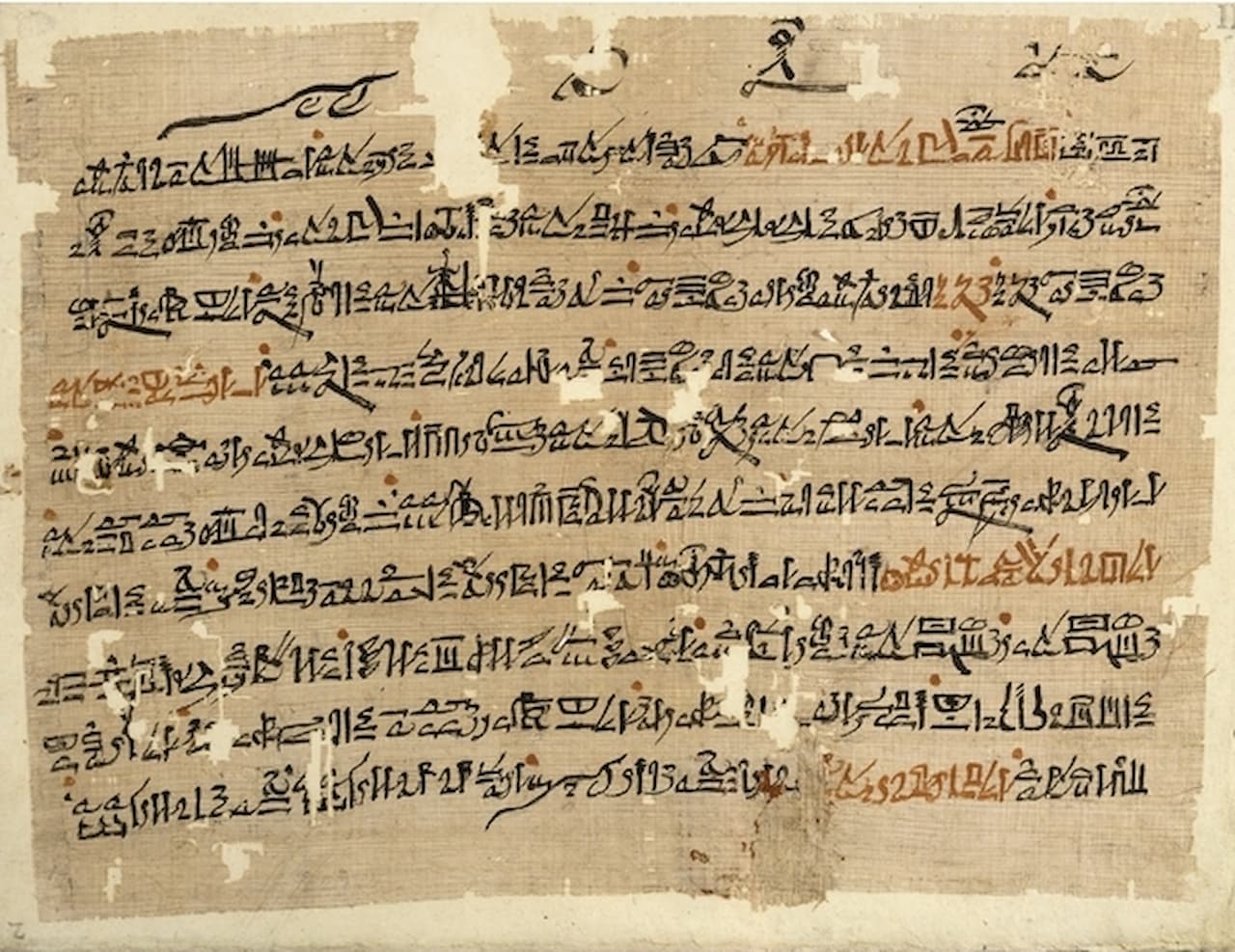

This ancient text survives today in its entirety in the Papyrus Sallier II, preserved in the British Museum. It remains a subject of debate among Egyptologists, some of whom question whether the text is truly satirical. Others wonder if the same author may have also written The Instructions of Amenemhat, another instructional text from the period.

Jurjens plans to continue her research into ancient Egyptian education, with many more texts still waiting to be studied. She reflects on the strange possibility that, much like the Egyptian scribes, the exam papers of her own students might one day be examined by scholars thousands of years from now.

SOURCES

Myrthe Timmers, Education in Ancient Egypt: ‘Everyone Used the Same Text’(Universiteit Leiden)

Wikipedia, Sátira de los oficios

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.