No one should be alarmed by the title of this article because it has nothing to do with Nazism. We are going to talk about the Shìjiè Hóngwànzìhuì, an expression that is usually translated as the World Red Swastika Society, which refers to a Chinese philanthropic institution founded in 1922 as an imitation of the Red Cross, adapted to the salvationist religion practiced by the Daoyuan sect (also called Guiyidao).

Daoyuan, or the Way of Return to the One, was created in 1916 as a syncretic faith that aimed to combine the typically Asian values of Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism with the Middle Eastern values of Islam and the Western values of Christianity to worship a universal deity called Tian.

It did not start from scratch but was a new attempt at something that had already begun in the early 20th century by the Xiantiandao sect, which was itself inspired by a movement that originated two centuries earlier in northern China under the Jin (or Yurchen) dynasty and was called Quanzhendao.

Daoyuan (which originally went by the names of the institutions that represented it, first Daodeshe and later Guiyi Daoyuan, until its final name in 1921) emerged in Shandong province under the leadership of Wu Fuyong and Liu Shaoji, quickly spreading to Beijing and other regions thanks to its acceptance by government circles. It even made its way to Japan, where it became linked to the Omoto-kyo Shinto sect. The precepts were recorded in a religious book titled Taiyi beiji zhenjing, and its activity was organized into six sections: administration, meditation, writing, texts, preaching, and philanthropy.

The latter found its most visible and famous expression in the founding (in the Renxu year, the eleventh year of the Republic of China’s calendar, equivalent to 1922) of the Red Swastika Society, launched by three of its most prominent members: Qian Nengxun -the first president-, Du Bingyin, and Li Jiabai.

After obtaining the approval of the organization’s president, Li Jian Chiu, they modeled it after the charitable and relief-oriented mission of the International Red Cross.

They also imitated its logo, replacing the cross with a swastika of the same color. Although it was the Hitler regime that turned the Parteiflagge (the Nazi Party flag -black on a white and red background-) into the state emblem of Germany, giving it worldwide recognition, the swastika was actually a very ancient symbol, as its name itself, derived from Sanskrit (suastíka, with various translations related to happiness, health, good luck, and overall positivity), demonstrates.

Swastikas have been found in seven-thousand-year-old reliefs, with a wide multicultural distribution from India to Greece and Rome, through Persia, pre-Columbian America, and so on. Sometimes it appears with its arms oriented to the right, in which case we speak of a right-facing swastika or swastika proper, like the Nazi one, and other times to the left, in which case it is a left-facing swastika or sauwastika, like the one used by Daoyuan, which we are discussing.

Of course, in the Far East, the swastika lacks the political connotation it has inexorably acquired in the West. Almost all religions there, from Buddhism to Hinduism and Jainism—therefore, in countries where they are practiced, such as China, Japan, India, and others—use it in their artistic iconography, decorating temples, homes, cars, and businesses without fear of causing confusion because, in addition, it is depicted straight, not tilted like the Nazi swastika.

In China, it constitutes a writing character that can be translated as “infinity” and is associated with creation and the manifestation of the divine, which is why Daoyuan chose it for the flag of the World Red Swastika Society, which, like that of the Red Cross, is depicted in red (a metaphor for an “innocent, bright, and radiant heart”) on a white background.

However, this institution, like its model, was—and still is—much more than its emblem, carrying out vast philanthropic work in line with one of its slogans, “promote morality and practice charity”: shelters, scholarships, soup kitchens, hospitals, retirement homes, orphan adoption, vocational training centers, aid for the disabled, fundraising for charitable purposes, and general relief missions, especially during disasters such as wars, earthquakes, typhoons, floods, etc.

As its focus was cross-border and internationalist, these efforts were not limited to Chinese soil but extended to other countries where they had opened offices (Paris, London, and Tokyo), promoting Esperanto education among its members for better communication.

They also provided assistance to those affected by major natural disasters, such as Japan (after the devastating Kanto earthquake of 1923, which helped spread the society’s presence there) or the Soviet Union.

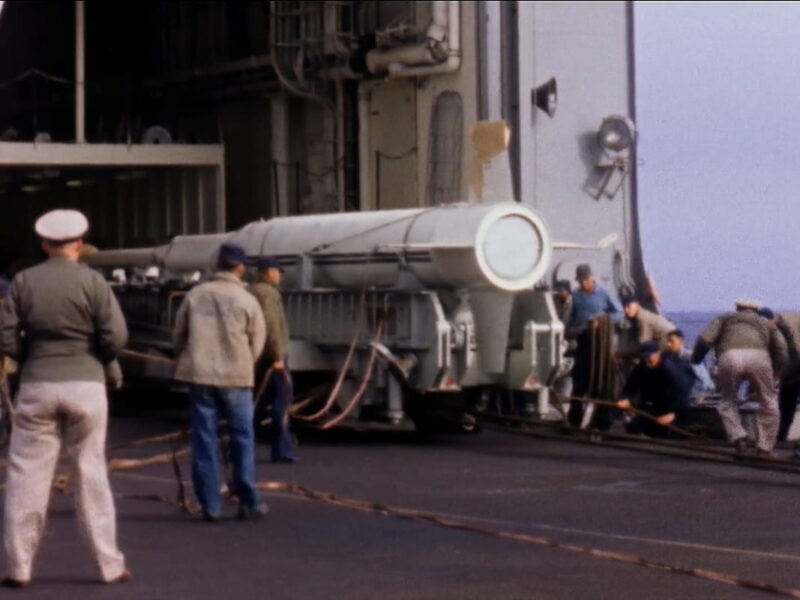

Nationally, one of their most remembered and well-documented actions was during the Nanjing Massacre, which took place in the Chinese city of the same name—then the capital—between late 1937 and early 1938, after it was occupied during the Second Sino-Japanese War by the Japanese imperial army. Soldiers carried out widespread rapes and killings among the population, with the number of victims estimated between one hundred thousand and three hundred thousand.

The World Red Swastika Society intervened to bury the bodies, and its president, Tao Hsi-Shan, who had a reputation for being calm and upright to the point that he stayed in the city during the battle, made great efforts to protect the citizens. The society’s archives in Nanjing are today an important documentary source for locating mass graves and studying that episode.

This selfless work, which fascinated many missionaries and attracted numerous Christians, helped to spread Daoyuan. After two decades, in 1927, it already had thirty thousand members, which skyrocketed to between seven and ten million a decade later. This growing strength did not sit well with Mao’s communist government, which eventually decreed its prohibition in 1949.

As often happens, Daoyuan remained alive in clandestinity within mainland China, receiving authorization to reopen its main office in Hong Kong in 1995.

It is there, in the neighborhoods of Tuen Mun and Tai Po, where it opened a primary school and a secondary school. Outside this Chinese special administrative region, the bulk of its activity is centered in Taiwan—home to the intercontinental headquarters—and other countries that received Chinese populations following the diaspora caused by World War II and the communist regime, primarily Japan, Malaysia, Singapore (where a third secondary school was opened), Canada, and the U.S.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on September 29, 2023: La Sociedad Mundial de la Esvástica Roja, la antigua organización china creada a imitación de la Cruz Roja

SOURCES

Wang Ying, Sociedad Mundial de la Esvástica Roja durante la República de China

Sociedad General de la Esvástica Roja-Taiwán

Wikipedia, Sociedad Mundial de la Esvástica Roja

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.